Room For Craft

MAY 2016: ALLISON BARNES

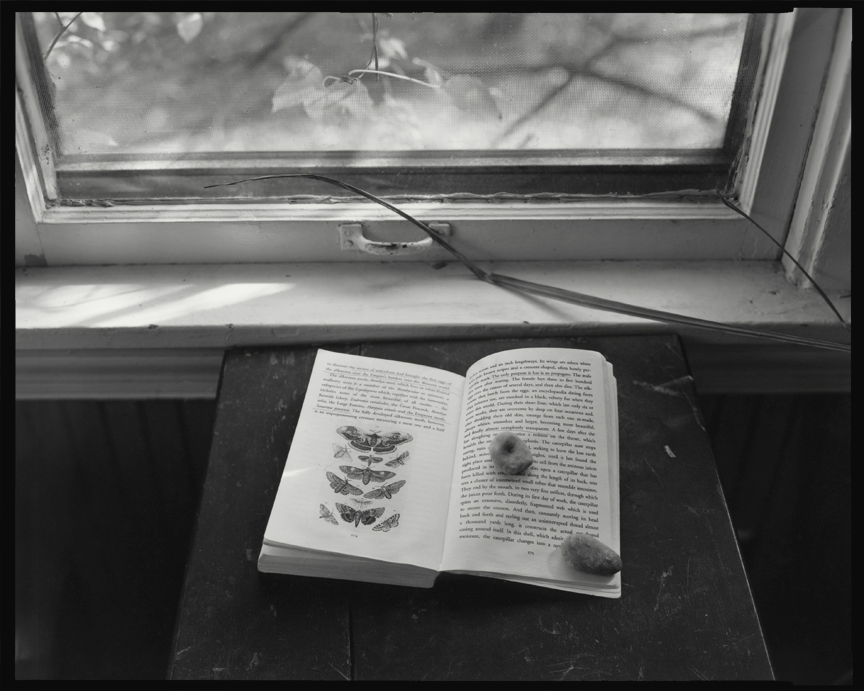

Pepper Flower, 2012

Allison Barnes is a photographer, fine art printer, and writer currently residing in Chicago. She is the co-founder of the darkroom Great Northern Labs, and her work has been featured in Aint-Bad along with other publications. The Hopper discovered Allison’s work at the Vermont Center for Photography where her series on place, Neither For Me Nor The Honey Bee, was exhibited in January of this year.

In a virtual interview, Allison and editor Sierra Dickey wrote long, inquisitive emails back and forth to one another. The edited and polished result of those emails is the following interview.

Sierra Dickey: Have you always worked as a photographer/writer/printer?

Allison Barnes: I identify most as a printer, though I am interested in how images are viewed in all forms, including web-based imagery, when it is appropriate. My interests lie within the physical object, the tangible image, and printed text.

SD: You have traveled to a few places (at least in the US) to photograph. Is there a particular place, town, or region that you consider especially significant to you? One you’d call home, or one that you’re otherwise seriously affected by?

AB: I think I owe my way of looking to my formative years in a rural town in New Jersey. I believe that we naturally hold on to the place we call “home” due to its lasting effects in our memories, and it’s through that preservation of place that we are able to perceive our own histories and take them into new spaces. I’ve had the distinct feeling of being “home” when I have been very far away from such a place, and that is something that I tend to tap into.

A Native Display in Tall Grass, 2014

SD: I’d love it if you could write more on this connection between preserving place and perceiving our own histories. By preserving place do you mean preserving those deep feelings of home, or a certain vernacular of space/time relations? What parts of your own history do you recognize as being especially tied to place?

AB: I love that—“the vernacular of space/time.” The familiarity of place is something that lives deep within us and extends far beyond the objects that we keep.

Perhaps for me, the act of collecting objects and images is a way of saying “I was here, this happened, this was . . . ” I am not as interested in preserving a feeling as I am in taking a piece of factual matter that can be used to depict specific encounters and details that describe a landscape, one in which our history was marked. We all have different modes of marking history and varying methods for storing it. Lucy Lippard once wrote that space makes up a landscape, but when memory is attached to space, it become a place.

When I was four years old, my father had me and each of our immediate family members put our hands in cement on the floor of a new structure he built on our property. That house has long since been sold, but in 2012 I returned to it and was amazed to see that our imprints and initials are unchanged, as though they had been waiting for one of us to return. It was really something to see physical evidence of my history etched in a location. That is just one example of my index within the landscape, but I believe that our histories are always tied to place, not just physically, but phenomenally.

SD: Speaking of specific places and their phenomena, in the series that showed at the Vermont Center for Photography, there were a few pieces that seemed to center around a cottage. I have my own fantastical ideas about the location based on the images, but where was this cottage? Did you live in it for a time?

AB: It’s interesting that you think that. I suppose that makes sense because Neither For Me Honey Nor the Honey Bee is very much centered on the idea of home, about what makes an intimate space and the myriad ways that the concept of home enters our personal landscapes. This collection of images is made up of moments and details that were present in various locations, such as my property in Savannah, Georgia, and then my house in Chicago, Illinois, after I relocated. Some were taken while living in a campground in New Mexico or when I was staying in a trailer in Sonoma County, California.

Even though they were taken here and there, my goal was to commemorate the attachment that one has to home; it travels with us to distance places. Our dwellings may change, but the ideology and mythology of home never does.

A Native Display with Scratched UV Glass; hair, wildflower honey, ladybugs, string, 2012

SD: One or two of the images were titled Native Display. Is this a term that you’ve seen elsewhere or is this a particular idea of yours?

AB: For me, the term references the local: to turn the landscape into a still life by displaying its natural history through objects or by simply showing a scene of a native landscape or its bi-products, such as honey, insects, grass, etc.

It also references a factual way of looking at things, which is followed by a list of what you are looking at. I don’t want the images to appear fictional because they are very much based within experience, the act of looking, and the ability to reflect on a specific moment.

SD: In that way, a “native display” is also a bit of a joke, right? It pokes at how contrived and artificial other indoor still life set-ups can be (velvet cloth, pears in a bowl, pewter pitcher) by showing how beautiful and really quite stately a happenstance “display” can be. Or, is it more of a tweak in perception: bringing the idea of the artful display and transposing it onto details in the out-of-doors to get people thinking? I enjoy the factual piece of it too. It seems like a serene way of looking at a scene or collection of objects as facts about a place or moment.

AB: I agree with the happenstance of a display—how one can find beauty in everyday objects that make up our environments or in the objects that speak about experience. A native display is not only about giving a sense of place to the objects, but it is also about how place offers gifts and revelations. Certain objects preserve place—we gather things such as rocks, shells, honey, and photographs that represent an experience. The title functions as a metaphor for the ways in which objects become collections and signifiers of one’s perceived history.

SD: Apart from Sappho, who was central to your artist’s statement for this series? What other authors/thinkers/artists have informed your ideas about space and place? Your suggestion that places are accumulations reminded me of Yi Fu Tuan and other humanist geographers.

AB: The title is an entire poem by Sappho, or at least what remains of that poem. Neither For Me Honey Nor the Honey Bee is also an ancient proverb, which means to take the good without evil. But when I read that poem, I think of how Sappho found material within individual moments, and then I think about how honeybees do the same thing. She leaves the hive—her home—to navigate the landscape to bring home nectar, pollen, and water. She determines her life and productions based on the flowers she finds and how far she travels. To collect images, memories, pollen, and nectar is very physical, just as experience and perception are physical acts.

SD: I’m curious how the things collected end up blended together in your mind. Bees take the pollen and process it into honey, and humans take memories, objects, and experiences and fuse them into a self/a personality/an attitude/a life. Not all of it gets blended, as some things like negatives, photographs, and talismans stand out and apart, but overall, there’s a melding, no?

AB: I think the key word for me is “collection.” There are reasons why we hold value in gathered stones, summer insects, or the way light falls through a window. I am interested in those intimacies that we feel towards a place and how a photograph is a form of processing those skirting memories.

Haircut in the a.m., 2014

SD: How do writing and your visual work relate to one another? Are they symbiotic or are your processes there physically and conceptually very different?

AB: My art practice certainly goes beyond photography, and writing is a great way to balance my creative needs. I consider myself a printer mostly because the printed image is extremely important to me, whether it’s postcard size or a mural on a wall. But text and images do have a symbiotic relationship, and I enjoy exploring their relativity to one another. Generally, my prose is about other artists’ work, as a way to understand it further and to educate others about it as well. I usually enjoy writing about place and space, or the themes of topophilia in general.

That being said, my next book is mostly text with a few images and not at all prose-like. For me, the process of writing and printing are absolutely conceptually linked, and this is a big part of Great Northern Labs—to combine text with images, to see how they play with one another when they are in a book, on a wall, or on the web, and to show how language is innate to the use of imagery.

SD: I’m curious if you ever think about text and the image as barriers to experiences in place. Are language, thinking, and the natural world all parts of one whole to you, or do you hold them apart in any serious way?

AB: We are constantly interacting with images and text and archiving them in one way or another. I wouldn’t say that they create barriers to experiences, but rather the opposite: we use what we know—those collected memories and acquired images—to navigate the natural world.

Language and thought are gifts that we obtained from our surroundings, from the stars, and from images drawn in the landscape. But the fixed image, the one that we can return to in a book, on a wall, or in our hands is rather marvelous. And what is even more wonderful is when your image carries cosmic implications for someone else.

Rings of Saturn, 2013