Room for Craft

DECEMBER 2020: ALLISON HUTCHCRAFTAnother Way to Feel Alive:

A Conversation with Allison Hutchcraft

by AMIE WHITTEMORE

Amie Whittemore: First, congratulations on Swale being selected for publication with New Issues Press as its Editor’s 2019 Choice! Swale is a highly textured, beautiful book and I look forward to examining its layers with you in this conversation. Section I of Swale is rich with images of illusion, images that then proceed to haunt much of the collection overall: in Section I these illusions are brought on by fever (as in “Calenture” and “Scurvy”), but also by desire for the world to appear differently than what it is, most prominently in the final, astounding poem of this section, “The Mermaids at Weeki Wachee,” where women

learned to perfect

strings of subaqueous tricks:

drinking bottles of Grapette and snacking

on bananas, turning their bodies like slow-movingFerris wheels, rubber flippers hinged

to their feet.

I am curious about this tension between reality and perception and how poems are artifacts of this tension: every time a simile is used, reality is bent to the speaker’s perception of it. Can you speak to how you became interested in this theme: was it something you discovered as the manuscript took shape or a preoccupation from the start?

Allison Hutchcraft: I think I have probably always been preoccupied with illusion. There is the wished-for world, and then there is the life lived. The space between the two seems very much a place for poetry. Sometimes, a moment in the “real” world, in my lived life, can feel so intense that it almost becomes unreal, and I can only contend with it, fit it into the boundaries of language, later, in a poem.

At the same time, I am a firm believer in things: the cicadas whirring outside my windows just now, the blast of a car horn, corrugated tree trunks, asphalt after rain. The facts of our world—the spaces we move through, the bodies, human and otherwise, we encounter and depart from—are essential. Of course, that doesn’t necessitate clear-seeing. As you said, through the sieve of the mind, through language, everything changes.

When I first read about calenture—a mind/body sickness that prompted sailors to yearn for, and even hallucinate, land—I was overtaken by the idea of this condition, which felt so recognizable to me, though I have never lived at sea. I realized how many poems I’d already written dwelled in a tension between illusion and reality, and from that realization, more poems grew. The more I wrote and read, the more this tension emerged.

An example. An early poem in Swale takes a quotation from Charles Darwin as its title: “‘I have written myself into a Tropical glow.’” Darwin wrote this in a letter to his sister in 1831, when he was just twenty-two, as he was anticipating a voyage to the Canary Islands. I find it fascinating that the “glow” young Darwin was enthralled by emerged from his anticipation of seeing the tropics—not yet his direct experience of it. He had been for some time obsessively reading Alexander von Humboldt’s writings about the Americas, and this immersive reading spurred in him a deep desire and longing, and a powerful imaginative life. This, in turn, engendered my own “Tropical glow”—illusion inside illusion. I love the messiness of all that, the overlapping: a young scientist in imagination’s trance, then me, centuries later (and very much not a scientist!) enthralled by that light.

Amie Whittemore

Allison Hutchcraft

AW: Relatedly, I am curious about the speaker(s) in the poems. In the opening poem, “Calenture,” the speaker begins: “I shouldn’t like to think of them, but I do— / the men who spent their days as sailors.” And, later, the speaker in “So I Try to Picture the Priests,” notes, in imagining priests pillaging turtle eggs for oil, “Their hands keep filling. I don’t / look away. Eggs, moons laid in sand.”

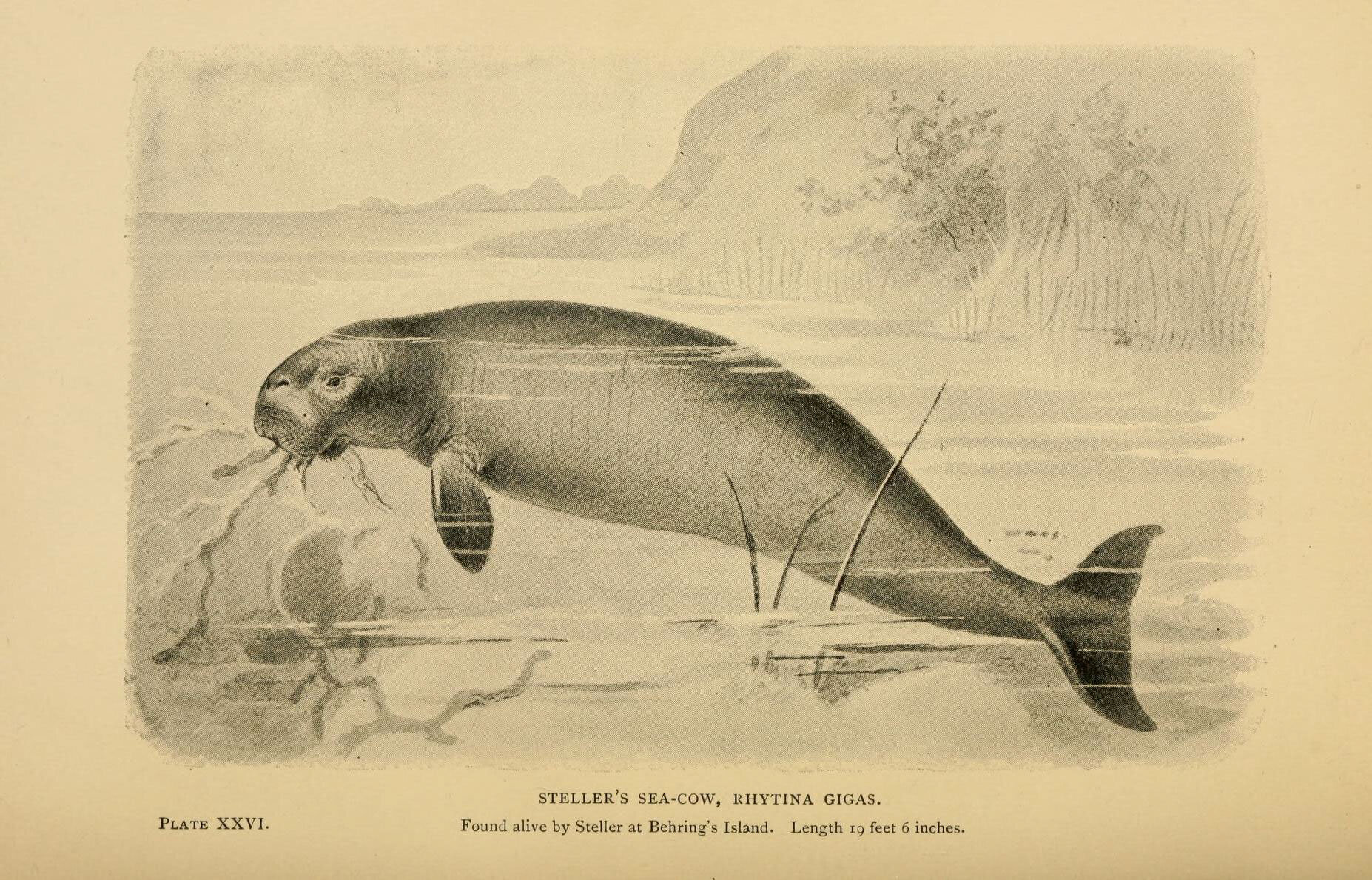

In these examples, as in other poems, the “I” feels fraught, hesitant in the role of witness: at times seeming uncertain of being an accurate witness, while at other times uncomfortable with relishing the challenge/pleasure of witnessing often brutal acts (I’m thinking also about “Steller and the Sea Cow,” how the dissection of the sea cow is so richly, sensuously described: “the plush mammary glands released / what was left of their milk” and “the sticky lachrymal sac, large enough to hold a chestnut.”)

At still other moments, the speaker becomes complicit with the sailors, colonizers, naturalists she watches, as we see in the use of plural first person in “On the New Continent, Our Eyes Shining.” Then the opening poem in section II is called “The Trouble is I,” explicitly calling attention to the complicated figure the “I” plays in this collection.

There’s so much to unpack here, about the role of the speaker, so I welcome anything you want to say on how you decide on a point of view in your poems. How would you describe the “I” that shape-shifts and drifts through and orders these poems?

AH: The “I”—as a point of view, as an impulse of where to begin—often feels fraught to me. Your description “hesitant in the role of witness” seems very true of my speakers, and of me, as I could not have been a direct witness to many of the things I write about. When imagining historical moments far removed from me in time and space, I often want the “I” to be on the edge of the poem, present but at the periphery. In “So I Try to Picture the Priests,” the first-person pronoun only appears in the title and final couplet, along the hemlines of the poem. Of course, that too is illusory, as the speaker is inventing everything in between! Subjectivity cannot be erased, however much the “I” recedes to the edges.

One major point of fascination for me in reading about figures like Humboldt and Georg Wilhelm Steller was how much their passion for the natural world—their sheer amazement at it, their electric desire to get up close to and understand it—was bound up with acts and perspectives that were enormously violent and destructive. Humboldt is credited with shaping Western environmentalism, and, indeed, he was propelled by a deep love for the natural world and spoke out against Europeans ravaging ecosystems in South America. Yet his role as a “discoverer” helped obscure the enormously complex indigenous systems of knowledge that already existed long before him. When Steller, the lone and lowly naturalist on Vitus Bering’s shipwrecked expedition, studied the sea cow, he had no idea that such expeditions would lead to the sea cow’s extinction just thirty years later. This makes me think of other, modern iterations of the same impulse, as Jamaica Kincaid notes in her brilliant A Small Place, where she writes, “A tourist is an ugly human being.” This seems as true of so-called explorers during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as the tourists flocking to Kincaid’s native Antigua in hopes of pristine beaches, island character, and luxury deals.

I was thinking, too, of what Renato Rosaldo calls imperialist nostalgia, “where people mourn the passing of what they themselves have transformed.” Rosaldo describes this kind of nostalgia, rooted in colonialism, as taking many forms, including when “people destroy their environment and then worship nature.” He says, “imperialist nostalgia uses a pose of ‘innocent yearning’ both to capture people’s imaginations and to conceal its complicity with often brutal domination.” As a poet, I have built my life around a deep belief in imagination and its power to make us feel and see the world in radically altered ways. In light of Rosaldo’s argument, however, that same power becomes destructive and terrifying.

As a white American, I am complicit with colonial naturalist figures even as I try to critique them. And so, I think the speakers in these poems shift in the tides of this complicity. Sometimes, the speaker is closer to me, the poet imagining and horrified by what she sees; other times, I take on the pillager through a persona voice, as in “On the New Continent, Our Eyes Shining” (which arose from reading about how Humboldt and his crew captured young monkeys after killing their mothers, and, in an especially grisly affair, pushed horses into electric-eel infested waters to see first-hand the power of those deadly currents). It’s easy, I think, to recoil from such violent appetites, but part of what I wanted to do was lean towards that violence, and imagine how the speaker might be part of it, so as not to disavow that complicity. Thus, when describing Steller dissecting the sea cow, I wanted to get as close (in language) as he was to that enormous animal body, to lean in and smell the carcass, cut down beneath the layers of fat, in order to reveal one intimate study while not obscuring the other reality we now know: that if you kill each animal you encounter, there will be none left, no matter how much you love and revere it.

In the more personal, non-historic poems, the “I” is probably fraught as well. Can one be a tourist in one’s own life? Maybe, especially given the unreliable moods of memory. In “The Trouble is I,” the speaker is experiencing such intense emotion that she does not feel like herself. There’s a fracturing, a low-grade dissociation, in this poem and others, and I hope a fraught “I” helps capture that feeling of breakage.

AW: A sequence emerges in Section II: the “As” sequence, in which nonhuman speakers inhabit the poems. I love these poems, the way they are bright openings in the manuscript, allowing multiple perspectives to co-inhabit the collection. I am also curious about the animals featured: sheep, foal, twin horses, foxhound—all domestic animals (which is in contrast to the wild animals presented in Section I, at times inhabiting the border of the wild and the tamed; I’m thinking of “On the New Continent, Our Eyes Shining”: “the animals we love most / we put in cages”).

You and I have spoken about our love of series. Can you talk about how this series developed? How/when did you see this series working alongside the other poems in the book?

AH: These poems are, by far, some of the oldest in the manuscript. Originally, they were self-portraits, although I eventually dropped that ornament from the titles. The self is in these, of course, and, inevitably, the human, but writing them I just relished imaginatively inhabiting the worlds of these animals. Sheep, horses, and foxhounds are, as you point out, all domesticated animals, whom we make work for us in some way. Their worlds overlap with ours, which offered a kind of shared language that seemed less possible in the poems figuring wilder animals.

A friend once remarked that Swale’s second section has a fairy-tale quality, which I feel is true. While the other sections feature oceans, precipices, and edges that blur, in Section II the poems are land-locked, enclosed. There are forests, fields, and cloisters—a domesticity and heady air, a closing-in. When ordering the manuscript, I felt immediately that these forest/field/cloister poems needed to be together, offering a landscape amid the surrounding seascapes.

I love writing series, although it’s always possible that some—or all!—such poems can ultimately end up on the cutting room floor. That can be painful later, but, in the midst of creating, I love how a series insists: you don’t have to embody all your ideas in one poem; you can proceed and explore from a variety of angles. There is not just one way.

AW: The title poem, “Swale,” arrives in Section III and is one of the most heartbreaking and vulnerable poems of the collection; in it the speaker expresses such union with landscape; so often the speaker seems to be a removed but careful/caring witness, but that division is erased here (and the erasure of this division, or the attempt to erase it, haunts this section). The speaker notes,

Swale also meaning a depression, a low place

in the land [...]

When I swale, I cannot

tell border from border, land

from water. I feel the loam

of day

crumble.

Here, once again, land and water switch places, but this time we feel this switch differently—it is not observed in feverish sailors but in the speaker herself. Still, while this poem, and much of this section, feels more personal than other sections, Swale is not confessional or post-confessional, modes that have been trending for decades now. Your work feels more akin to the work of Elizabeth Bishop, Brigit Pegeen Kelly, and Joanna Klink, poets for whom the traces of lived life are faint on the page. Can you speak to how you decide what from your life makes it into your poems?

AH: What a thrill to be thought of amidst Bishop, Kelly, and Klink, such brilliant, masterful poets! Thank you. I deeply admire their work, as I do your description of those “traces of lived life” “faint on the page,” which captures beautifully how their poems often feel to me, too.

One of the things I love about poetry is how intimately it can bring us into another mind’s unfolding. The poems I most adore do this: they unlatch a new kind of thinking, set in motion, unbidden, unexpected movements of mind. As a reader, that feeling is incredibly thrilling, and personal. This too, a poem offers, is a way to feel alive. I have no idea if my work affects a reader in a similar way—though that is the hope!—but, in any case, the attempt to do so feels very personal.

Even my poems that are steeped in research document in some way what it felt like for me to be alive at that point, and how I tried to make sense of it. The personal seems indivisible from the poem, my obsessions and fears and longings always threaded into the fabric. I realize, though, that autobiographical “facts” are probably tough to glean! Which is perfectly fine with me. I admire poets who bring their lived lives overtly into their work—naming friends and loved ones directly, for instance—but it rarely occurs to me to do so, beyond addressing a “you,” which always feels intimately charged. I suppose I approach a poem more as a palimpsest of interior life, of what is imaginatively and emotionally lived. Some image or memory or deeply felt catch-in-the-throat announces itself, even during the day-to-day, and I want to get back to it through a poem. This could be described as a lyric—rather than narrative—impulse. The underside of a leaf, or, more abstractly, the shadow that leaf makes. That secret to which the self keeps wanting to return.

AW: I adore the final section of the collection, “So Legged and Footed,” which offers a long sequence of poems about the dodo; this closing section brings the collection full circle: we begin with colonialism, with the exploitation of lands, people, plants, and animals, and end where such expansionist, greed-driven behavior always ends: in extinction, the dodo going extinct in 1681, due to human interference. This section casts a backwards light across all of the animals that populate the collection, from the lamb to the fiercely mating otters and the dead sea cow.

And, so I think of John Berger’s essay, “Why Look at Animals,” where he writes, “That look between animal and man, which may have played a crucial role in the development of human society, and with which, in any case, all men had always lived until less than a century ago, has been extinguished. Looking at each animal, the unaccompanied zoo visitor is alone. As for the crowds, they belong to a species which has at last been isolated.” Is Swale, fundamentally, a collection about this isolation, about how the farther we spread across the planet, the more alone we render ourselves?

AH: I love that you quote this essay from Berger, which I have thought about often. This is a great question, and it reminds me of the notion of “species loneliness,” which Robin Wall Kimmerer describes as “a deep, unnamed sadness stemming from estrangement from the rest of creation, from the loss of relationship. As our human dominance of the world has grown, we have become more isolated, more lonely when we can no longer call out to our neighbors.” I do think isolation—and, more so, loneliness—is a major subject in the book, although I have not thought about it as arising specifically from expansionist/colonial spread. Did colonizers during the age of empire feel lonely? Maybe, although I’m not sure in the ways that Berger and Kimmerer describe. Or, perhaps their methods of assuaging loneliness were just all the more brutal and destructive.

Berger also argues that, long before the zoo visitor became isolated, the closeness between human and animal may have been “the proximity from which metaphor itself arose.” He posits that, “If the first metaphor was animal, it was because the essential relation between man and animal was metaphoric.” I find this fascinating. With metaphor, there is an intrinsic gap between things, and a longing to bring them together. I read Berger after I wrote the first poems in this sequence, and Kimmerer long after I finished it. And yet: longing, isolation, and metaphor course through the poems.

Why did I want to think about the dodo? Why did I feel an affinity with this bird, centuries extinct, from literally across the globe? It’s irrational, beyond reason. I found myself making the relationship between speaker and dodo impossibly familiar, even writing, “I miss you.” How can we miss that which was never known? And yet: we do. The dodo is always referred to as “you,” that pronoun of personal address, which can be singular or plural. I liked that malleability, and ambiguity, too: the dodo always personalized, addressed as the dodo, sometimes even a particular specimen like the Oxford Dodo, and yet inevitably all dodos at once. It betrays, perhaps, something of our human imagination: one bird becoming all the birds of that kind. As is often the case in poems, the “you” cannot speak back. The address is one-sided. There’s loneliness there, too—the usual gulf between “I” and “you,” a space that will not close.

The dodo has been widely appropriated by our human world; its image is not its own anymore. This is deeply problematic, yes, but perhaps also one way to register loss. The United Nations recently reported that one million plant and animal species are facing extinction. The mind boggles. And yet while the heart may ache, the loss feels unspecific. Maybe looking at—or thinking about—animals can help activate some part of our imaginations, and, in turn, empathy.

AW: These poems are rich in historical and observational detail; the “Notes” section points to your thorough research. I also wonder how much the poems are informed by primary research. Can you speak to your relationship to both primary and secondary research: does research precede drafting or vice versa? How does time in the field inform your creative process?

AH: Time in the field (a phrase I love!) is, for me, vitally important. Sometimes, that field is a place in nature—woods or coastlines where I walk, notebook in hand—and sometimes it is a place I travel to through reading.

I always write by hand first, in my notebook. It’s a messy affair: bursts of free writing, images, and, when secondary research is involved, quotations and details I learn. Sometimes, the core of a poem emerges in one such writing session. More often, it grows over the course of various days. Real drafting for me starts when I move from notebook to computer, knitting the pieces together, ignoring initial language that doesn’t work. At that point, I am focused only on what will make a poem. If I go back to the field, or to secondary materials, I go back to the notebook, too.

AW: Swale is your first full-length collection, one I know you’ve been working on for years. I’d love to hear about your process: how do you cultivate patience and persistence in your writing practice? And, also, how did you know when Swale was finally done?

AH: This is such a great question—and one I am always hungry to hear poets respond to! Swale was, as you said, a long time coming, in part because, while writing its earliest poems, I was still very much learning about myself and poetry. My time in graduate school was essential for me, yet most of the collection took form afterward, after I moved to a new state, began a new job, and slowly wrote, as they say, in the cold. There were periods when I did not write much, as well as immersive periods following an obsession, and occasional bursts of production. Various people and places have been my creative islands—my poetry group in Charlotte, dear friends (like you!) with whom I’ve exchanged work from afar, a few crucial residencies. Without such touchstones, and the connective tissues to other people reminding me that to create is a human act and impulse, it can be hard to keep going.

I am a slow writer, but I fear not a patient one! I’m always wishing that things would take less time, arrive more dramatically. And yet, grudging student of patience that I am, looking back I can see that waiting got me through. Early iterations of the manuscript were not good. I had to learn to be alert to new directions poems were taking me, and shed poems I no longer believed in. Two junctures now seem pivotal, the first of which was learning about calenture. When I heard about those nautical hallucinations, I felt certain a poem about it would open the book (even before I had drafted anything, which now seems like a lot of pressure!). That central image of land and water switching places, and intense emotion shaping visions of the natural world, was already alive in so many poems, but I needed to stumble upon calenture first. Another crossroad: realizing Swale was my title, and writing the title poem. It took me years (and many uncomfortable titles) to realize that it was the name of the collection. About the time I did, I was heading to my residency at Sitka, which, with its forest-meeting-sea setting, was the ideal place to write “Swale.” All of this seems easy to say now—that writing “Swale” would happen as I’d hoped, that land and water mixing would become a central tenet—but I don’t want to diminish the real uncertainty and doubt I felt while writing. Yet some kind of momentum eventually took hold, and I could feel the book coming into its final, natural form. I had to wait for that momentum to happen, and to learn to trust that, eventually, it would.

Amie Whittemore

Amie Whittemore is the author of Glass Harvest (Autumn House Press), the 2020 Poet Laureate of Murfreesboro, Tennessee, a 2020 Academy of American Poets Poet Laureate Fellow, and Reviews Editor at Southern Indiana Review. Through her laureateship she is partnering with Southern Word to offer Write with Pride, a series of poetry workshops and open mics for LGBT+ teens in Rutherford and Davidson counties. A lecturer at Middle Tennessee State University, she holds degrees from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Lewis & Clark College, and Southern Illinois University Carbondale. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in The Gettysburg Review, Blackbird, The Missouri Review Poem of the Week, Cold Mountain Review, and elsewhere.