Room for Craft

NOVEMBER 2017: AMIE WHITTEMORE

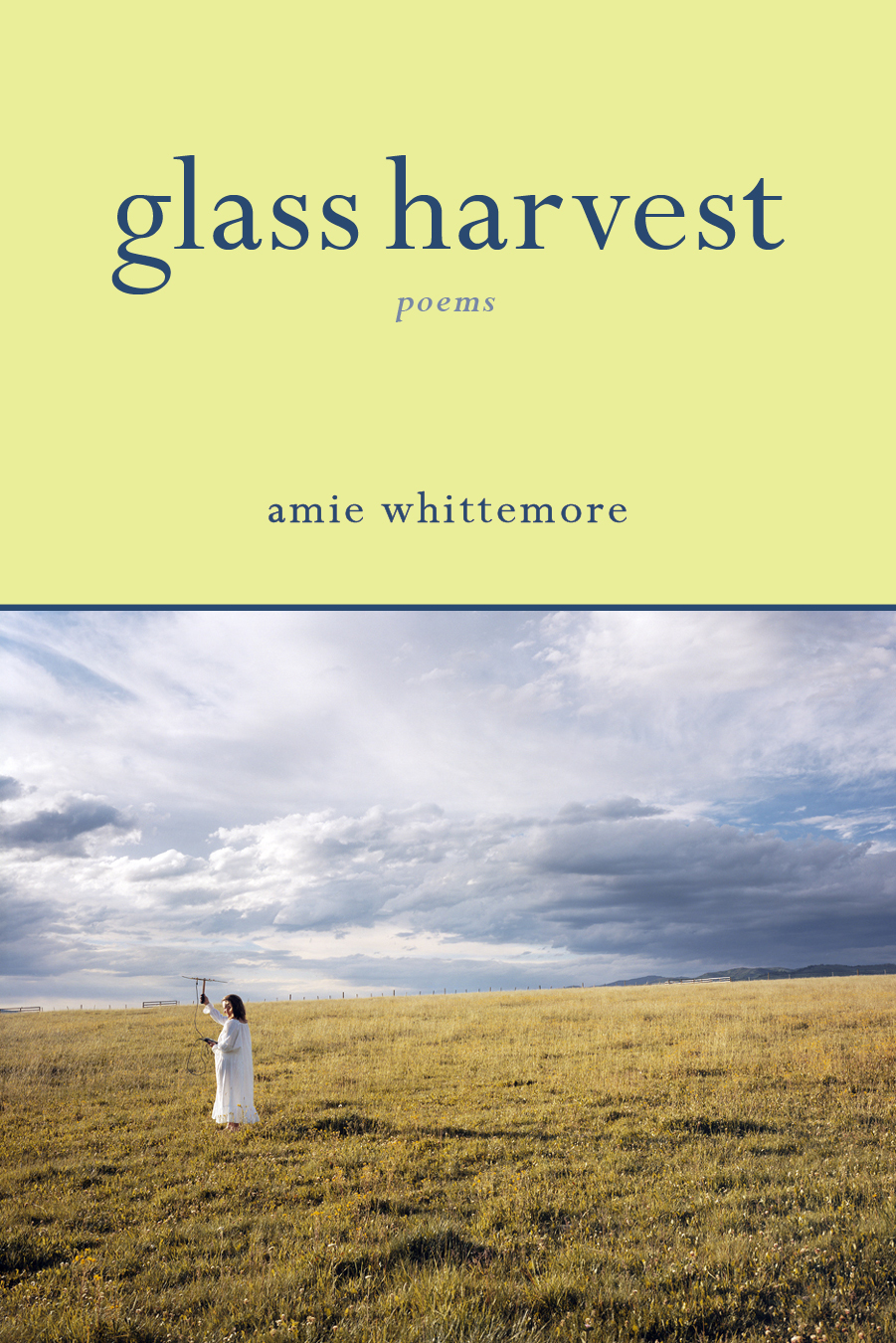

Amie Whittemore is a poet, educator, and the author of Glass Harvest (Autumn House Press). She is also co-founder of the Charlottesville Reading Series and assistant editor at Poem of the Week. An instructor at Middle Tennessee State University, she holds degrees from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (BA), Lewis and Clark College (MAT), and Southern Illinois University Carbondale (MFA). Her poems have appeared in The Gettysburg Review, Sycamore Review, Rattle, Cimarron Review, and elsewhere. David Nilsen spoke with Amie about her process and her new book. The landscape images, from St. Anne, Illinois, near where Amie grew up, are by Mike Schnell.

Your poetry is deeply interwoven with nature and wild imagery. Can you tell me a little about how the natural world informs your creative process and what that looks like when you're crafting a poem?

I spent my childhood steeped in the outdoors—I had a pasture to roam, creeks to leap, half-abandoned barns to explore. As a kid, these places were full of mystery and discovery; as a teenager, they were places of solace and retreat. And, while my adult life has been spent mostly in urban/suburban environments, I still find, as Wendell Berry notes, “peace in wild things.” I walk around my neighborhood each evening, admiring my neighbors’ gardens and the starlings roosting in Bradford Pear trees. Which is all to say, my access to and experience of nature and wild imagery has always been in conversation with the domestic and tamed: there’s nothing wild about a cornfield, but there is something wild about watching a deer disappear into the long green arms of that field, in the way its scent peppers an entire summer.

As for what this looks like as I’m crafting a poem, it often looks like nostalgia. I miss having my own garden, my own yard, more unfettered access to spaces that are less obviously cordoned by human activity. I return to former landscapes often in my dreams and these returns often end up in my poems. I also, like my cats, spend a lot of time staring out of windows and listening to the sounds of my current neighborhood—the many church bells, the neighbor kids jumping on a trampoline, are all filtering into the new poems I’m writing. My poems often feature imagery that is a blending of lived, remembered, and dreamt landscapes.

I like that you mention nostalgia in reference to these poems so saturated with nature images. As I read Glass Harvest, I kept noting the different ways nostalgia gets expressed in these poems. In a poem like "Yard Catalog," you're just listing these evocative images, and while all of them feel wild, many of them show a human hand. Human effort, given time to decay, can melt into a wild place and become part of it. Can you talk a bit about the kind of hardscrabble rural nostalgia that informs these images in your writing?

I love that phrase, “hardscrabble rural nostalgia,” and I agree with your statement that given time, the human and the wild do melt into each other. Sometimes I feel like I was born nostalgic and sentimental about loss: I was the eight-year-old kicking stones across the playground when my best friend moved away. This quality, perhaps more than my rural childhood, is at the crux of my writing more than anything. While I do miss rural living—particularly the way it encourages one to be attuned to the many nonhuman life forms that share our world, with the change in seasons, with solitude—I think I would be nostalgic about wherever I grew up.

It can be easy to see nostalgia as a distracting force—it can tend to romanticize what is distant in favor of what is close at hand. All of this is why I seek to investigate it. Too often I make myself feel guilty for feeling nostalgia or other fraught feelings. Glass Harvest was an exercise in trying to remove the hood of guilt from nostalgia and its gang, an exercise in a kind of permission-giving—here are life’s griefs and beauties and it’s okay to love them tremendously, recklessly, and adamantly. I am not a fan of letting go, or at the very least I’m very bad at it. I am, however, in favor of creating space in the self and the heart. For me, that means creating space for what I’ve lost—family members, a spouse, the rural Illinois landscape I adore—alongside the loves, landscapes, and adventures that are here, that are yet to come. The heart is a reluctant mansion, more expansive than it cares to admit.

I guess there's a way in which most poetry is, to some extent, driven by nostalgia, in the sense that our impressions and images come from memory in one way or another. Speaking to the way ecology sits in your poetry, do you think ecology and ecopoetry demand nostalgia to some extent, especially in our current climate situation that looks rather grim?

This is an issue to which I have given a lot of thought. First, I am fascinated by the ways in which people are inventing terminology to deal with the trauma of climate change and mass extinction. I’m particularly interested in solastalgia, the concept of missing something in your home environment that is lost due to climate change and/or the encroachment of development: that it is not you that has left something (which is what I think nostalgia points at), but that something, seemingly larger and more long-lasting than yourself, has left you. We feel abandoned by the havoc we are wreaking on the planet. This sense of abandonment is, obviously, in direct conflict with our culpability: these losses are entirely our fault and yet so huge we feel victimized by them (and of course, many peoples, on islands and in less-developed nations, are direct victims of what industrialization has wrought).

It is a deeply uncomfortable, unsettling, and disempowering feeling. Language often feels inadequate, though I know many excellent poets are investigating these issues in their work (a few of them read recently at the University of Arizona). I also am fascinated by the way language is evolving to cope with this unprecedented global trauma—The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows is a trove of this budding lexicon.

So, to sum up, yes, ecopoetry often demands a backwards gaze and seeks to create solace, to preserve, to attend to the fraught moment. However, having just read Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, I think it is also important to acknowledge the complexity, resilience, and otherness of the planet’s future. Her analysis of the trade patterns surrounding the matsutake mushroom, while not exactly what I would call hopeful, does look at “ruined” landscapes as places of potentiality; disturbance is inherent in the environment—there is no pure state. Thus, while the rate of destruction and change we are experiencing is unprecedented and crushingly certain, what isn’t certain is how we and other life forms will adapt, what windows will open as doors shut. I try to hang on to the fact that while humanity’s inadequacies have gotten us to this place, it’s also likely we are just as inadequate at imagining both the horrors and possibilities that lie ahead.

I think this way in which ecological nostalgia is poised between an idyllic past and a bleak future is echoed in how you handle nostalgia elsewhere in Glass Harvest. You often express a bittersweet nostalgia over things that haven't even happened, a sort of anticipatory nostalgia. In a poem like "To My Future Granddaughter," you express melancholy over losses that haven't taken place yet, and you use the repeated image of eggs in several early poems as symbols for hope deferred, possible futures mourned in advance. There's a song by Over the Rhine that has the line, "Tell me this welcome peace isn't dancing with the ghost of future tears." That emotional space seems to define much of this collection.

Yes, I feel like much of Glass Harvest inhabits a space between losses and is trying to reconcile hope with the inevitability of loss and grief. On an intellectual level, it’s a complex and fruitful challenge to consider; on a personal level, it is less inviting in its complexity: how do you keep your heart open? How do you resist your own self-protective measures? How do you risk? And then, there’s a kind of horror that sets in when you realize you will encounter, and survive, so many losses; it’s unbearable that it’s bearable.

Both ecological nostalgia and personal nostalgia oscillate between the “idyllic past and bleak future.” It is impossible to separate our own fates from that of the planet; I haven’t studied ecopsychology deeply, but find it essential to how we move forward. To take care of ourselves, we must take care of our planet. One of my professors in graduate school, Greg Smith at Lewis and Clark College, said it was important to think of the world not as something we can save, but as omething that can be healed. Shifting our mindsets toward what heals our relationships to ourselves, to each other, and to the earth seems vital at this juncture in our history.

You point out in "Aphorisms," the book's first poem, that "The tax you pay for loving is grief," and I think that's true both in personal relationships and in our relationship to the Earth. In the very next poem, "Dream of the Ark," you acknowledge, "I know I'm a fool for whatever's gone away," pointing out the unique way nostalgia works on you. Together, these find echoes throughout the collection in which you speak of nature in terms both tender and grim. And yet in several poems—"Another Beach Poem," "To My Future Granddaughter," "Autumn Thinking"—you express that you envy nature and wish you could be a more natural piece of it rather than human. How does that sit with your awareness that nature is so damaged? What does it mean to envy nature?

Your observations point to the folly of nostalgia—sometimes it points to something that never existed (or maybe it always does so, in a way). Certainly, in the poems you mention, where the speaker envies nature, it is a kind of nostalgia—a kind of longing for a type of life that is foreign and thus, seemingly, removed from the challenges of being human.

It is also a longing for a way of existing that is not so charged with damaging other life forms. What other species has made the world so wildly untenable for so many other living things? The guilt of being part of that—and, the compounded guilt of loving humanity, even loving the conveniences and innovations that are the downfall of ecosystems, cultures, myriad livelihoods—is, for me, exhausting, and the poems try to get at that feeling. To be anything besides human seems, potentially, to be innocent in a way that is otherwise inaccessible. I hope foxes do not wake up and worry about the impact their daily meals and waste products have on their ecosystem.

I think the key there is worry, that most human of activities that is inherently one of inaction, of tension without release. I imagine oaks do not worry, nor finches. At least I hope not.

And, of course, I do recognize that invasive species wreak havoc on ecosystems; they only do so because we helped them invade. I used to resent starlings, English ivy, and that favorite of the contemporary Southern poem, kudzu, but really they are stand-ins for us. They are the footprints of global capitalism—who am I to blame them for thriving where we planted them?

"Drowning the Marigold" feels like the spiritual center of Glass Harvest, beautifully pulling together so many of the themes of the collection into one evocative reflection. Can you share the genesis of this poem, and, if possible, use it as a way to walk us through your writing process?

“Drowning the Marigold” is a quintessential representation of my writing process. The poem stems from an actual memory that has haunted me for many years: while I never drowned a marigold, I did drown a sapling my brother planted from a seed from an apple he’d eaten. It had been a random act on his part, and I was admittedly jealous in a weird, childish way—I was the kid who was obsessed with plants, he certainly wasn’t. So, my family was leaving for vacation and it was my job to provide my grandmother instructions on watering the sapling. I told her to water it too often and it was dead by the time we returned. And, while part of me realized I was sabotaging the sapling, part of me was oblivious to it—thus this memory has stuck with me, highlighting the strange ways we can be both intentionally and unintentionally cruel to each other.

That story is way too long and convoluted for a poem, so I had to sharpen it to its essence in the writing process. In doing that, I discovered how this idea of “drowning the marigold,” of sacrificing something lovely because you can’t bear its eventual demise, intersected with other preoccupations and the poem began to come into focus.

“Drowning the Marigold” also is indicative of the often autobiographical nature of my poems. While my poems often start from an autobiographical place, they generally reside, as this poem does, in a limbo between fact and invention. This playground where fact and make-believe intersect and combine in new and surprising ways is my favorite geography to inhabit—in writing and, more often than not, in life.

David Nilsen

David Nilsen is a writer living in Ohio. He is a member of the National Book Critics Circle, and his writing has appeared in The Rumpus, The Millions, The Collagist, Rain Taxi, Open Letters Monthly, and many other publications. He lives with his wife, daughter, and very irritable cat. You can follow him on Twitter as @NilsenDavid.