Room for Craft

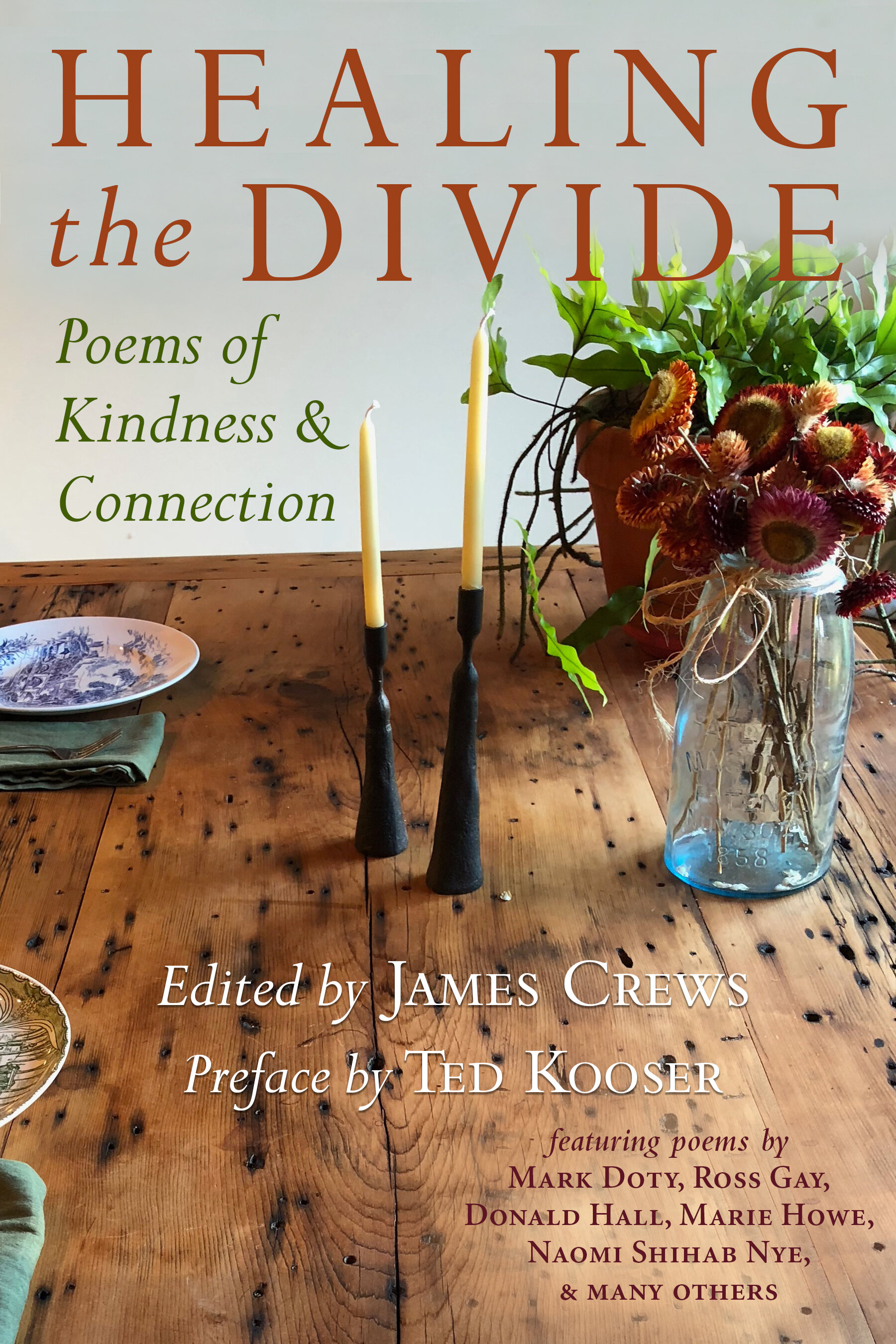

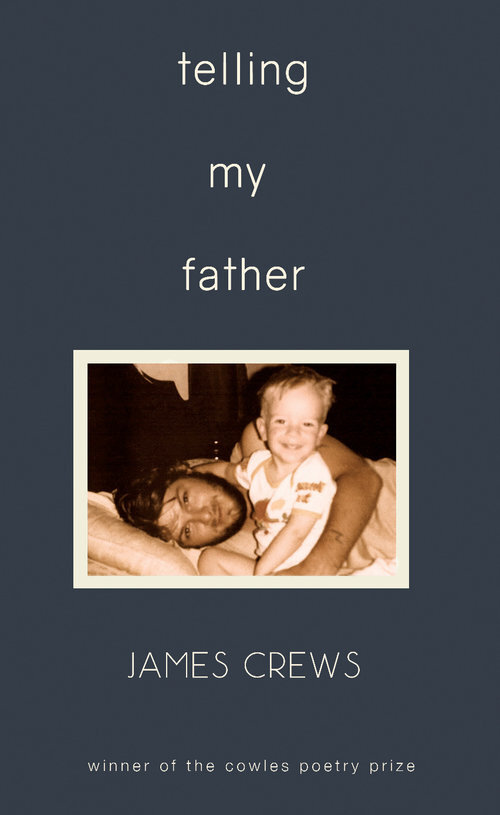

SEPTEMBER 2019: JAMES CREWS In celebration of National Poetry Month, Montpelier comes together as PoemCity, with daily events organized by The Kellogg-Hubbard Library. Nicholas James attended Bear Pond Books for a reading from the collection Healing the Divide, edited by James Crews. James is the author of two collections of poetry: The Book of What Stays (Prairie Schooner Prize and Foreword Book of the Year Citation, 2011) and Telling My Father (Cowles Prize, 2017).James's work has appeared in Ploughshares, Raleigh Review, Crab Orchard Review, and The New Republic, and he has contributed to Ted Kooser’s American Life in Poetry newspaper column and The London Times Literary Supplement. He fosters the writing of others through Mindfulness & Writing workshops and retreats. In addition to being an exemplary literary citizen, he is a proud Vermont resident, living in Shaftsbury with his husband, Brad Peacock. Nicholas spoke with James about the new collection, his writing, and what he does to support the writing of others.The title of the anthology Healing the Divide is beautiful and nuanced. What was it like lining up pieces to come together under a moniker so rich in potential meaning?

Assembling this anthology of poems about kindness and connection was a work almost entirely of intuition. I somehow just knew that I wanted to arrange the poems alphabetically, and quite early on, I had a sense that I wanted to begin the book with Ellery Akers’s “The Word That Is a Prayer,” about the use of the word Please, and that I wanted to end the anthology with Miller Williams’s shorter piece, “Compassion,” which seemed to encompass exactly what Healing the Divide was trying to say—that it’s best to be kind and compassionate to others, since we have no idea what unseen battles they might still be fighting deep inside. Even though the poems were arranged alphabetically, however, I do feel there’s a rhythm to the book, and each poem feeds fairly logically into the next. As with my own creative work, I’m always trying to achieve a kind of narrative and flow, and how I go about this is not entirely explainable, but readers do seem to pick up on it.

Sticking with that final poem “Compassion” by Miller Williams, it is just gorgeous and really hit me in my soul, which is appropriate considering the final line that describes, “where the spirit meets the bone.” Were you conscious of choosing poems that might be more spiritual in nature?

I think your response to “Compassion” is absolutely appropriate, and in some ways, each of these poems is ultimately spiritual in nature. I feel that kindness is its own form of spiritual practice (the Dalai Lama has said, “Kindness is my religion”), and so each of these poems captures a scene, a moment, or a feeling in which some deeper connection occurs. I often come back to the poem “Small Kindnesses” by Danusha Laméris as well, in which she calls those “moments of exchange” that we share together “the true dwelling of the holy.” I love that idea that we create a kind of temple or church whenever we come together with others in a tender, caring way. Maybe that’s one of the reasons that Danusha’s poem has gone so viral in the past few months; that single poem has been shared by tens of thousands of people on social media, and has been featured on Tracy K. Smith’s podcast, The Slowdown, and will also be read by Garrison Keillor on his podcast version of The Writer’s Almanac. Her poem really strikes a chord with readers who are hungry for deeper messages like these, especially in the times we live in.

Another poet of tremendous impact is Ted Kooser. He is a former mentor and teacher of yours. How did the connection that you formed with him during your time together lead you to want to have him help with Healing the Divide? Did he approach you about the project?

When I first got the idea for this anthology, inspired by my husband’s run for the US Senate in 2018, I approached Ted about writing a preface. He had already written another preface for me for an anthology of mindfulness-nature poems that I hope to publish next year, and he has been incredibly supportive in the years since I graduated from the PhD program at University of Nebraska, where he still teaches. I also worked with him and his assistant editor, Pat Emile, on the American Life in Poetry newspaper column, which appears online each week. This was the project he began during his tenure as US Poet Laureate, and it continues to this day. As I say in the Acknowledgments of Healing the Divide, working with him on that column helped to teach me how to be a better editor and writer. I got a chance to hone my skills by choosing poems that would be resonant and accessible to as wide an audience as possible. My years of working with him also taught me to comb through literary magazines and newly published books, looking for the best poems for the project. I would also like to say that Ted Kooser is one of the kindest, most generous human beings I’ve ever met, and even in his eightieth year, he continues lifting up the work of other poets, and publishing his own excellent poems. His latest book, Kindest Regards: New and Selected Poems, gathers his work from the last forty years, and it’s a revelation of a book. One could learn a lot about writing poetry from going through that collection.

In the introduction you share that the anthology arose out of your own searching for stories “of people coming together, bridging the gap and healing that so-called divide between us to share instance of kindness and vulnerability.” You began to share the poems you found on social media and then the idea of putting them together for the world in one book came to you. Can you speak to that realization and the excitement and other emotions you felt in it?

I have always used social media as a platform to share poetry and other inspirations in an effort to help people slow down and appreciate the actual world. But I soon realized that when I started sharing these specific poems about kindness and connection, the response was overwhelmingly different. People really seemed to need to read about instances like these, to remind themselves that kindness was still out there, and that people were paying attention to it, doing their best to highlight it. Poetry doesn’t do that often enough these days, in my view, and it’s a missed opportunity to connect with an audience in a deeper way.

In several of the poems, the reader is invited into a scene in which the connection the speaker shares with the natural world is evident. These include “Before Dawn in October” by Julia Kasdorf and “Winter Sun” by Molly Fisk. In the former the language of season is woven in with the strife of the speaker. In the latter the speaker is drawing palpable hope from a winter’s sun and tying it to our ability to come together. Were you conscious of advocating for protecting nature and the natural world against the advances of climate change when including these poems and others?

The subtitle of the anthology is “Poems of Kindness and Connection,” so I definitely set out to include poems that showcased a connection with nature, even if those pieces didn’t explicitly feature any other people. Being in nature, after all, is a form of kindness toward ourselves, and toward the world in general, especially as the earth continues to face destruction, through the relentless pursuit of profit and the ongoing climate crisis. The two examples you point to are excellent ones, though the poem that immediately comes to mind is “Remember” by Joy Harjo, who was just named our nation’s very first Native American Poet Laureate. Harjo writes: “Remember the plants, trees, animal life who all have their / tribes, their families, their histories, too. Talk to them, / listen to them. They are alive poems.” We are very much in need of this kind of deep listening right now because as a society we need to acknowledge the aliveness and consciousness of trees and clouds, of all plants and animals. It’s so easy for us to forget our interconnectedness with the natural world, and I knew that any anthology about poetry and kindness would have to include poems that point to our own “naturalness” as well.

Also included in Healing the Divide is a poem of yours named “Telling My Father.” It comes from a book of the same name and, I would argue, defines that collection. Can you speak to how a group of poems can come together through narrative into an almost meditation or conversation?

In some ways, I think of “Telling My Father” as The Poem That Saved My Life. I had written a version of it during an undergraduate workshop with David Clewell at Webster University, but it returned to me during a writing residency in Oregon over a decade later. I say it saved my life because it arrived at a time when I was filled with doubt about my abilities as a writer and nearly ready to give up. In some ways, it felt almost as if my father were speaking to me through the poem, reminding me of what was important. And when I did decide to write a book that is more or less an elegy for him, I felt it was essential that the poems “speak to” each other somehow, form a more cohesive narrative. I prefer books of poetry (and books in general) that tell some larger story, and I pay very close attention to how I arrange the poems in every new collection. I think of each poem like a gleaming shard of memory or insight, and the final arrangement as a kind of mosaic that hopefully allows a reader into my own heart and mind.

Running through Telling My Father is the theme of “want vs. need.” For writers who are beginning to see consistent themes in their own writing, how would you encourage them to approach those themes? How does a writer nurture something that is coming about naturally?

Want vs. need is definitely a theme throughout the collection, and much of my poetry. I guess another way of saying it is desire vs. need, something I explore quite often in my work. For writers beginning to find their own obsessions and themes, I recommend just letting them happen organically and intuitively. I often don’t notice some of those larger themes in my writing because I’m too close to the construction of the poems themselves, so I have to rely on a few trusted readers to point them out to me. For instance, with my first collection, The Book of What Stays, the titles of many of the poems and of the book itself came about because a dear friend pointed out that so many of the poems were about loss, framed as things or people leaving or staying. I’m not sure I ever would have noticed this on my own, or at the very least, it would have taken me much longer to see. So I encourage writers to be open and receptive to how others are reacting to your work, especially those you trust the most. In a typical workshop, there might be only one or two writers who really get what you’re doing. I’ve always cared most what they thought, and simply let go of whatever didn’t feel true.

Speaking of workshop and turning to your teaching, how have you grown and developed as a workshop leader throughout your career? In some listings you are named as a writing coach. At what point did you feel you could confidently identify with that title?

An events coordinator once accidentally called me a “writing coach” in one of the listings for a workshop, and I thought: I really like that title! Whether I’m a college professor, workshop leader, retreat facilitator, or visiting writer in a classroom, I do act as a kind of coach for people looking to get in touch with their own writing and creativity. I believe we’re all inherently creative in our own ways, and writing is just one way of touching on some of those deeper parts of ourselves that can remain hidden from our surface-mind for a long time. I’ve been teaching in some capacity for almost fifteen years now, beginning with my first creative writing class at University of Wisconsin-Madison, and I’ve grown by being as vulnerable and open as I can with my students, giving them the opportunity to know themselves and our world a little better through the practice of writing. I’m quite a shy, introverted person, so it’s never been easy for me to stand or sit in front of a group and speak, but the more I do it, the more comfortable I am sharing what I know to be true as someone who has pursued a creative life, sometimes at great sacrifice. But I can say it has always been worth it, and I wouldn’t change a thing. I only hope I can help others feel the same way about their own creative lives.

This coming fall you are going to lead a workshop entitled “Igniting Creativity” at the Green Mountain Academy of Lifelong Learning. Upon a quick glance at the title, I read it as “Igniting Curiosity.” Going with this misreading, in what ways do you feel curiosity and creativity go hand in hand? How vital are one for the other?

Curiosity is vital to creativity, and longer-lasting than an initial burst of inspiration. I was just talking about this very issue with a friend yesterday, in fact. If we follow our curiosity, I don’t think we’ll ever be disappointed, though this does mean giving ourselves the space and permission to simply “play” with words (or whatever media we might use for our art). I think Elizabeth Gilbert says something to the effect that it’s much more useful and pragmatic to follow your curiosity rather than your passion, as we’re often counseled to do. Passion can run out or change course, but if we’re simply holding onto the thread of what we’re genuinely curious about, there’s an openness of mind that results. We’re not as attached to outcome either. I might have an idea for a project, for example, and begin in earnest. But if I keep sticking to my idea of how I want it to look or turn out, I might miss some swerve that takes me to a whole new way of seeing my work. The same is true at the level of a poem, story or essay: you want to let the thread of intuition guide you, rather than imposing your own thoughts or expectations.

What do you feel is important for writers to remember as they try to build community and seek publication?

Publication is not as important as it might seem. Yes, if we are writers, we do want to find ways to share our work, but I know a lot of MFA graduates who stopped writing because they grew too discouraged about publishing or not publishing their work. In short, writing or any creative pursuit should never be about the outcome or the reward, in my opinion. This relates to what I was saying earlier about giving ourselves permission and space to play as writers. If we keep in touch with why we create in the first place, then we’ll never lose sight of our intentions, and it will make it much easier to seek out and find the community we need. In my experience actually, community has been far more important than anything else. This includes keeping in touch with teachers and fellow writers, but also creating a community of your own. You can do this by starting writing groups, offering workshops in your neighborhood or at the local library, and certainly by writing reviews of books that really speak to you. Book reviewing has connected me with far more writers than I ever would have dreamed, and I’ve become good friends with many of the writers whose books I first reviewed years ago.

Nicholas James

Nicholas James is a grateful New Englander who has also found solace in the sands of West Sands Beach in St Andrews, Scotland, and resonance in a cobblestone corner in Charleston, South Carolina. He is currently working on a collection of twenty twenty-lined poems centered on his cerebral palsy. He greatly enjoys being able to speak with other writers about what sparks their writing, including conversations with Caryn Mirriam-Goldberg and Matthew Olzmann for Hunger Mountain. At least once a summer while visiting one of his favorite beaches, he matches his age in number of waves body-surfed, usually without having to get out of the water and take a break. He tries to live by the motto “listen more, waste less.”