Room for Craft

MAY 2018: HEATHER SWAN

Heather Swan's creative nonfiction has appeared in Aeon, ISLE, Resilience Journal, About Place, and Edge Effects. Her poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in Poet Lore, The Raleigh Review, Phoebe, About Place, Midwestern Gothic, Basalt, The Cream City Review, and Cold Mountain Review. She received her MFA in poetry and her PhD in literary and environmental studies from University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she is currently a lecturer. Hopper poetry editor James Crews spoke with Heather about her new book, Where Honeybees Thrive.

I wonder whether you might begin by talking about your process for writing Where Honeybees Thrive. The book is meticulously researched and curated, so it must have been a labor of love for you over the course of several years—or as you describe it in your introduction: "part love song, part lament, part quest." What initially planted the seed?

Writing is the way I process my experience of being alive, and so I began writing about honeybees long before I knew I was writing a book because they have always interested me. They appear in my early poems and journals. After years of dreaming about keeping bees, I began to visit and apprentice beekeepers, to learn the art myself. I fell in love immediately and was reading everything I could find. At about this same time, it was becoming apparent that honeybees and other pollinators were in serious trouble. My desire to know what was wrong became a bit obsessive, and my passion really led me quite naturally down a path to discover how we might help them. The book was the result.

You cite your visit to China (described in Chapter Two) as one of the more surprising of the many journeys you undertook to write the book. You say: "I had heard that the Sichuan region had wiped out its pollinators with indiscriminate pesticide use and that the government's solution was to train people to be 'human bees.' The idea that humans could replace this nonhuman labor force seemed farcical to me." Most readers would agree, I think, and most of us would have expected a dire situation there as well, given the news out of China. Yet you found "fairly harmonious" places in both Yangshuo and Yingjing, which—for now at least—seem balanced and healthier environments for bees. Would you talk a bit more about your trip to China? Were there other surprises like this along the way?

China overwhelmed me for so many reasons. I have always admired Chinese brush painting and the landscapes found in those images. It was incredible to wake up in Yangshuo and be inside that landscape. I have also been a casual student of Buddhism for all of my adult life, particularly after living in Nepal, and so visiting monasteries and meeting Tibetan monks again were powerful experiences. But on a larger scale, I would say that China, like the US, has a lot of contradictions. We often see the dark side of their industrial sectors in the media, but what we don't talk about is the fact that they are planting trees, building solar panels, trying to save the panda, and that they have areas where the growing practices are—to my mind—wiser than the chemically dependent monoculture model we often practice.

In spite of the mounting evidence that pollinators face an uncertain and possibly grave future, your book strikes a hopeful tone (at least to this reader), even in its title. Was it difficult to maintain a positive outlook and to seek out those places in the world where honeybees remain alive and well against enormous odds?

Because I'm a person who reads and researches constantly about the tragedies our earth is undergoing at the moment, I do find myself feeling overwhelmed at times. In my work, the apocalyptic narrative is the dominant one right now. The project of this book was, in part, a survival technique. Meeting people who are so passionately committed to not just acknowledging that we are facing huge problems, but really thinking creatively and actively pursuing alternate paths for us made me feel hopeful. We simply can't give up. We need to remember that we can change our behavior if we want to do it. We just have to start. Hopefully the people I write about in this book will inspire readers to make changes in their own lives.

Additionally, I have to say that for me, one cure for anxiety and depression is to just go outside and look at the world around me. I frequently go to the woods or a nearby body of water to just listen and observe. The energy of the earth itself is very powerful to me. It both heals and motivates. Even in a city, we can look up at the ever-newborn clouds or the sunlight coming through the trees and reflecting in the windows of the buildings or the birds navigating our world. There is potential for awe in every moment really, if you slow down and drop into presence. So, for me, taking breaks and going outside is another way to manage the weight of knowing about environmental issues.

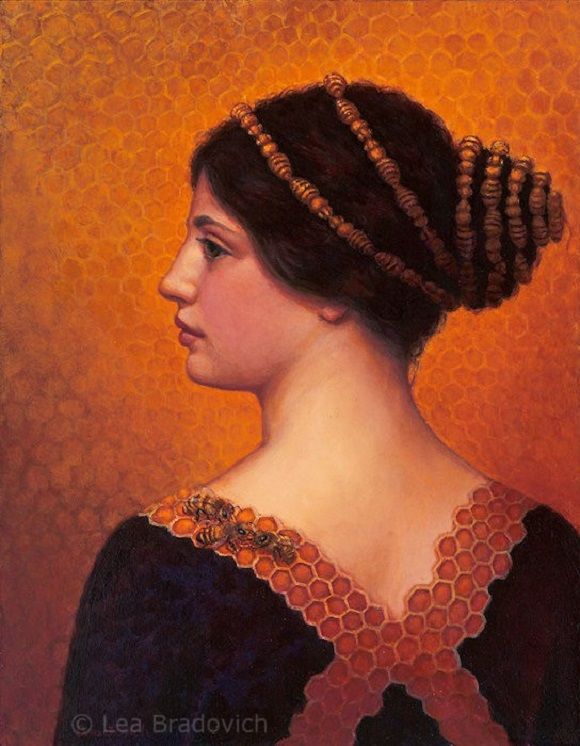

Lea Bradovich. Look Homeward Queen Bee. Oil on panel. 18 x 14 inches.

In the final chapter, you dissect the word hope (as opposed to faith) and cite what historian William Cronon has said with regard to the future of our planet: "We cannot teach hopelessness." You also end the chapter with these lines from a Max Garland poem: " . . . it's by cultivating wonder / the commonwealth is fed." Was writing this book its own cultivation of wonder or joy for you? This question seems especially relevant in the face of the "pre-traumatic stress disorder" that you say afflicts many climate scientists, and I wonder if you have ever faced something similar, given the number of years you've devoted to studying environmental issues during your PhD at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Cultivating wonder was absolutely part of this project. One thing I thought about often was: How do I get someone who is not interested in insects or is even repelled by them to become interested in them? I wanted my prose to mirror my own real experience of being in the presence of honeybees, which always puts me in a state of reverence. Donna Haraway has this idea about how at this moment we need to be "making kin" with the nonhuman. How do we best do that? To me, the experience of wonder might lead to respect and a more empathetic relationship. My hope is that the book will open people to the possibility of caring more deeply about nonhuman others, and maybe invite them to be more gentle/mindful in their lives to allow these nonhuman others to simply continue being.

Elizabeth Goluch, Bumblebee. Sterling silver, 14K and 16K gold, 7x7x4 inches. From the collection of David Weishuhn, Toronto, Canada.

Can you discuss how you came to use some of the artwork interspersed throughout the book? Speaking of reverence, I was especially moved by the magnified photos of bees by Rose-Lynn Fisher. The up close views of the wing-seam and proboscis (which "no longer looked delicate," as you point out) especially made bees seem more real and animal-like to me than they ever had before.

It took me a very long time to find all of the artwork for this book. To me, the work is much more than mere illustration or ornament. Each of these artists is offering a kind of argument that affects us differently than other forms of argument, like a list of statistics, for instance. In my own life, because I grew up with artists, art has always been one way of making sense of the world and of making meaning. The experience of seeing Rose-Lynn Fisher's work does shift our understanding, as you suggest, by forcing us to see the honeybee as, I would argue, sublime. Sarah Hatton's images made with dead bees overwhelms us, in part, with the sheer number of casualties, but also with the dizzying effect of the patterns she creates with their bodies. The Beehive Collective's illustration fiercely articulates what they believe we are doing wrong as a society. Sibylle Peretti reminds us of the innocence and wonder of childhood, but also clearly shows us the difficulty of trying to negotiate human and nonhuman relationships, a kind of beautiful yet still inharmonious relationship that leaves us longing to somehow recreate some kind of union or at least for us to work toward having a less destructive impact on the natural world. Lea Bradovich imagines what harmony might look like. Each of the galleries in the book offers something different and important.

I know that you are also an accomplished, award-winning poet, so I assume that you have used your own poetry as well to think through and process issues related to bees and pesticide use. What does the poetry that you included in your book offer readers that the prose cannot, or are they complementary?

I do think that the language of prose and the language of poetry are doing different work in this book. If you permit me to use a metaphor, I think that the prose is operating on the level of the meadow. It is filled with an array of different flowers and grasses. It's broad and various. The poetry, on the other hand, is more like honey, the distilled product of the nectar from one group of flowers. The poetry I have chosen offers the reader an opportunity to experience something special, intense, and rare. The poetry, like the art, invites an audience to understand and feel something that lives outside our day-to-day language.

Sibylle Peretti. St. Francis. Glass. 38 x 23 inches.

That's a gorgeous way of describing the difference between poetry and prose! I also find hope (or faith, depending on your preferred word!) in the ingenuity of the humans you interview, who are responding in healthy, creative, and compassionate ways to the challenges of growing ethical food these days. I was especially heartened by your profile of John Eisbach Jr. and his Wooded Wonderland blueberry farm, in which you describe the "startling" scene of trees that "appeared to be covered with tinsel." You go on to say: "I learned that John and his helpers had tied hundreds of feet of discarded VCR tape into the trees . . . Here was one of John's secrets of pest management. The shiny trees kept blue jays and deer away." They also play recordings of birds of prey on the farm to deter other birds from feeding on the berries. Are there other creative ways that we as a country, and as individuals, can respond to what amounts to a crisis for bees? What do you hope readers will take away from your book?

One of the problems for many important insects is that their habitats are disappearing. A very simple thing we can all do in our own communities is plant native flowers. Yards could be transformed into meadows. Medians between highways could be filled with flowers. Rooftops in cities can support gardens. In addition, we need to be more mindful about pouring pesticides and herbicides on our land. Many of those chemicals are not just harmful for honeybees, but when they seep into the groundwater, they affect algae growth, amphibians, and others. If we can begin to think of ourselves as part of an ecosystem and have an awareness that without the insects, the clean water, the clean air, whole ecosystems will collapse and we, too, will not survive, then I think our habits will change. And I see this happening. These changes are not just good for honeybees. They're good for the entire planet.

James Crews

James Crews’ second poetry collection, Telling My Father, won the Cowles Prize. He lives on an organic farm in Shaftsbury, Vermont, just a few miles from the Robert Frost Stone House.