Room For Craft

DECEMBER 2015: JOHN ELDER

At sixty-eight, John Elder enjoys becoming more associative in his thinking and writing than ever before. Along with Irish music and travel, conversation is a dear pastime for John and his wife, Rita, and something at which they are both clearly well practiced.

After a tour of their net-zero home in Bristol, Vermont, Rita and John talked with me and another Hopper editor over tea on Sunday afternoon about writing, playing, reading, and eating as various kinds of work in which they engage. We came looking to elucidate the physical needs and habitual rhythms of writers and thinkers and left with the tricks of musicians, cooks, and architects.

About an hour into the conversation, John brought up an old speech-giving trick that Charles Dickens reportedly used to wander around a subject whilst remaining on topic. You visualize a wheel in your mind and give each sub-topic a spoke. The main point is the axle, and as you go along in your speech, you turn the spokes in your head one by one, hopping from point to point and anecdote to anecdote without losing your way. After John explained that he often thinks and writes with this wheel in mind, I realized that he had indeed been operating the wheel in responding to our questions. Our question of him (the axle)—how writers make themselves able to perform their work—took three distinct points that on first listen might not appear to be related: throwing things away, music, and work identity. These are what you could call the tenets of John’s writing life.

A book of Ireland, the desk, and a colorful wall of nonfiction.

Give us a picture of your morning routine.

“I always make breakfast,” Elder begins. Coffee, homemade bread, peanut butter, and apple sauce are staples. Rita and he treasure a slow and comfortable morning: “We really like breakfast—and always light candles for it.” After eating, a second round of coffee is taken into the living room, where the two read poetry aloud to each other before engaging in the work of the day. They’ve made their way through Emily Dickinson, “have always read Frost,” and recently became enamored of Billy Collins. When Billy Collins came up, Elder stopped the conversation to grab Aimless Love off the shelf. He then proceeded to read us “The Lanyard.”

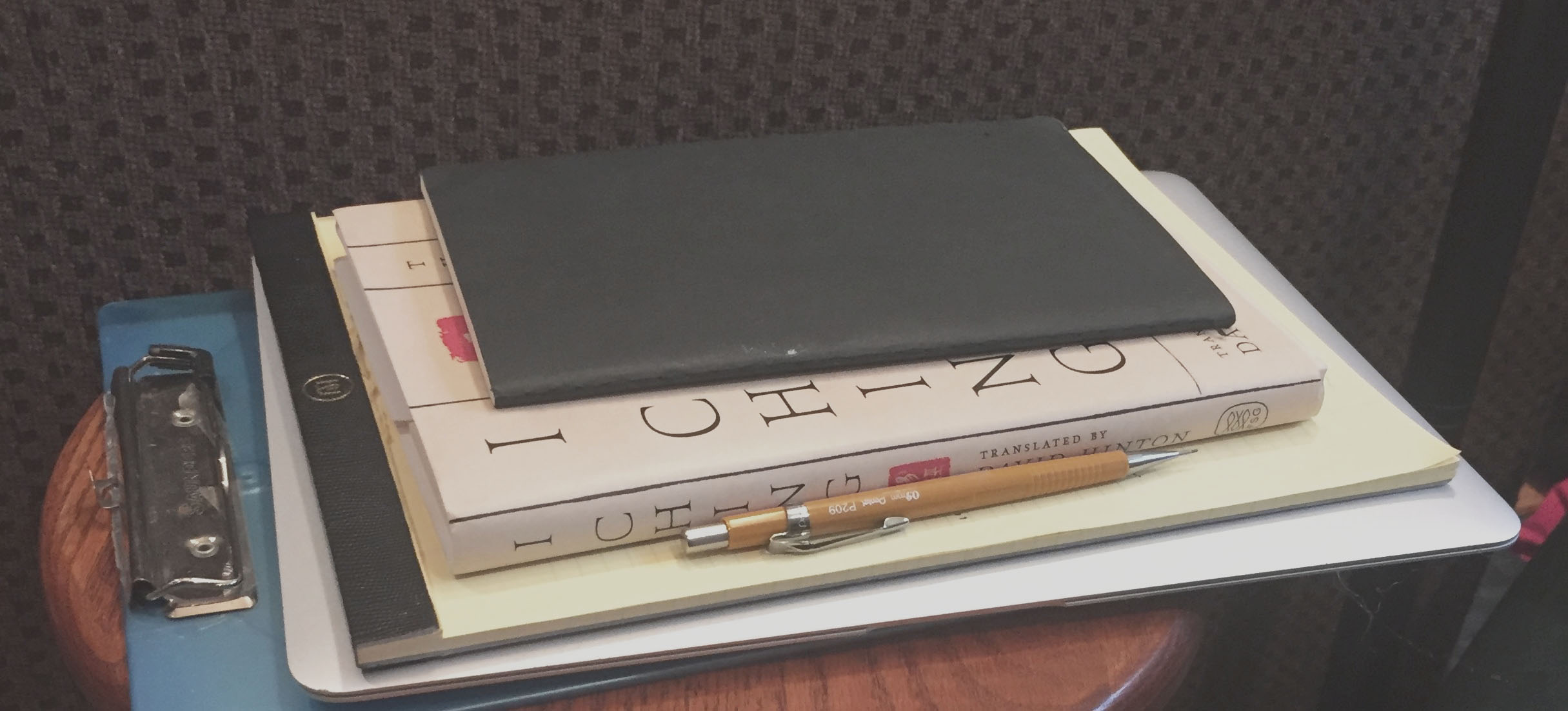

Before retiring from Middlebury College in 2010, Elder would write before eating in the morning. Now, he takes it easy. After walking the family dog, Shadowfax, practicing Qi Gong, preparing breakfast, and sharing poetry, he’ll finally descend to his basement study, where two humble bookshelves frame a wooden desk and evergreen leather chair. On most days, writing begins in the journal. On special occasions, when he’s captivated by a certain book (currently the I Ching, as translated by another Vermont scholar, David Hinton), writing begins by recording impressions on the text in a separate Moleskine.

Tell us about your work space.

Dimly lit, cool, and serenely quiet, Elder’s study is also the below-ground family room. His desk and chair take up a petite corner of the space where a couch, TV, and DVD collection also live. Above his desk is a Chinese ink drawing of a Taoist phrase, “mind like water,” along with a black-and-white portrait of Rita he took thirty years ago.

When we visited, the house was still rather new to them. Elder explained to us that in the move here they’d gotten rid of as much as possible—including books—and that this had made them “feel a little free,” even if it somewhat worried their grown children. The study, and the rest of the house for that matter, doesn’t feel ascetic or empty in a sanitized way, but rather extremely well curated. Every book, picture, framed map, and goat-bedecked throw pillow have earned their place. There’s very little detritus.

The green leather recliner in the corner is where Elder does most of his work. He told us that when he was in graduate school at Yale, his favorite room in the library had similar chairs, and he relished many a long evening spent in them. Years after, Rita and he stumbled upon this one at a yard sale and scooped it up quick for all its great associations.

John's workspace via John's hand.

What materials do you require to do good work?

“I do go in for all the little obsessive stuff,” Elder concedes. Personal writing begins in a Moleskine journal with a Pelican fountain pen. When he begins drafting a new essay, he moves to writing on narrow-lined yellow legal pads with a fine-point mechanical pencil. Certain pieces may also begin directly on the laptop, depending on their nature. “Sometimes you need to write fast, and sometimes you need to write slow.” Computer born-and-bred prose has a tendency to be “baggy,” but its gift of speedy composition can allow you to “trip into” unanticipated connections within your own work and other subjects. Fast typists can also write more. While working on his memoir, Picking Up The Flute, Elder was sometimes able to produce seven to eight pages in a morning.

Revising, however, is always done on printed drafts with the mechanical pencil. These few tools and the embrace of the green leather chair are the sum total of Elder’s material writing requirements.

How do you do work outside of your office?

“I’ve written a fair amount about landscape.” Earlier in his life, Elder would make observational journal entries out of doors, believing that there would be something “in” them that he couldn’t get elsewhere. Now, he prefers to take only sparse notes when in the field and return to his study to really write about the things he sees on excursions. This kind of two-step process allows for fusing: “things blend a little” into a richer whole.

Are you always thinking about your work, even when you’re not writing?

“Yes and no.” To Elder, writing and working on books and essays is not an act of “transcribing” thoughts or images, but “a discovery” towards his true point. “I’m a binge writer; I always have been,” he clarifies. “It all adds up somehow.”

If he couldn’t write for a month? Elder would be just fine. He would play the Irish flute more, practice Qi Gong more, work on the game of Go. Conceiving of writing as a dynamic process of thinking on the page led Elder to another key realization: all good work will have a surprising aspect. He described a “stockpile” of decent ideas that are openly available to all intelligent people, a Wikipedia of the intellectual realm. To make something interesting and new, though, something really worth reading, one has to go after what isn’t openly accessible. “You want something that will surprise you and galvanize you.” Writers don’t get to those sublime places by following an outline every time. When Elder outlines at all, it is usually in the middle of a work when he revisits his wheel and counts the spokes that have appeared so far. It’s those new spokes—the unforeseen connections—that make writing invaluable.

This kind of composition is not a one-step wonder, however. Elder insists that quick composers like himself must always be asking themselves where the center is, wondering about “intrinsic content,” and determining subcategories of the big idea. “Spinning around is fun for me,” but if he followed that hopscotching instinct to associate to its full extent, Elder believes he would quickly “lose all forward momentum.”

Although Elder certainly can write, and believes fully in the importance of the discovery that the act brings, he surprised us by identifying first and foremost as a teacher. That’s the work that he spent nearly forty years of life perfecting, and that’s the way he’ll always approach the world.

Your latest book is about learning music late in life. How do you think about music in relation to writing?

“Being too direct makes me squeak,” Elder laments. Thankfully, there are layers to music that help him avoid this in his writing. Since learning the Irish flute at sixty, and now writing about his journey into Irish music in Picking up the Flute, Elder says that “the music has suffused the writing in ways that are new to me.”

Both Rita and John had ample analogies to offer on this subject. Rita talked about the task of memorization in music (she plays the concertina) and how when one is learning a new tune, one must play it all the way through, over and over again, until the end, no matter how terrible it sounds. This kind of full-scale imbibing or absorbing of the piece is the only way to get the essence into your brain for memorization. The same goes for John in writing. He prefers not to self-edit as he goes. During drafting, worrying about the technical and the precise wordings of things can slow, or even block, his progress towards the heart of a piece. This reminded me of something I once heard Ariel Levy (another exceptional writer and craftswoman) say: “you can’t decide to have an idea.” Exacting composition (while other times necessary), if uninspired, can never result in the kind of compelling assertions that leave readers with all pores awake.

“It’s kind of like panning for gold,” John explains. Accumulating a certain amount of material (in music or on the page) can then be sifted through for the nuggets that surprise you with their gleaming. Rita reminds him that “it’s harder to throw things away if they’re polished.” Right indeed. Loose first drafts are easily disposable, and sloughing them away can leave one feeling “a little free” as they get down to the good stuff. All in all, John’s “amateur spirit” when it comes to writing has liberated him to do great work and reach new landmarks unencumbered.

Interview and photography by Sierra Dickey