Nonfiction

APRIL 2018

Searching for a Landscape Identity

by ELI J. KNAPP

“For a relationship with landscape to be lasting, it must be reciprocal.”

—Barry Lopez

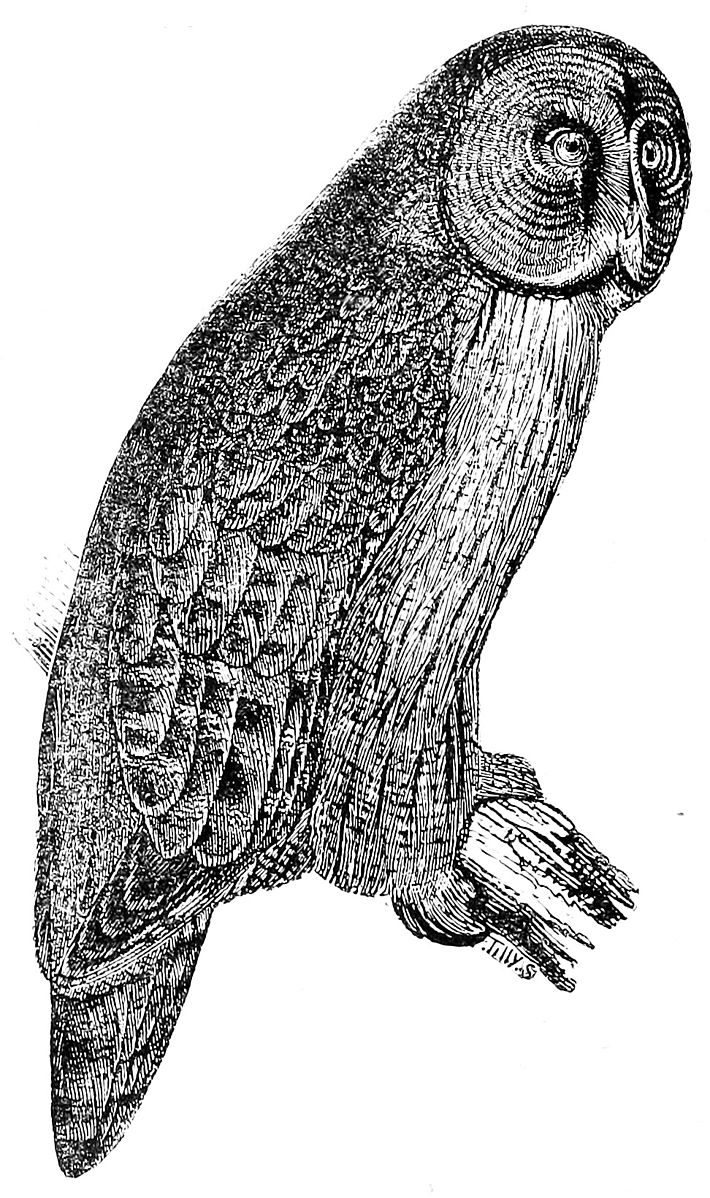

“Great gray owl!” my son, Ezra, shouted from the back seat. I hit the brakes and pulled over, Ezra and I craning our necks out the windows.

“Nope,” I said, lowering my binoculars. “Barred owl.”

“Gimme your bins, Dad!” Ezra demanded, his absence of manners almost as troubling as his incredulity. I glanced at him in the rearview mirror. Here was a scientist—a born skeptic—squeezed into a nine-year-old body. “Guess, you’re right,” he finally conceded, handing back my binoculars.

We were slightly deflated. Granted, any owl was cool. But we were specifically after a great gray, undisputed Zeus of the owl pantheon. Although exceedingly rare, we had expected a great gray here in this nondescript meadow in the mountains of southern Oregon. Why? For a simple reason: I had seen one here before.

Other birders have confessed they share in my suffering. It’s a common, yet chronic, disease. The symptoms are straightforward, but the cure, if there is one, isn’t. It goes like this: If you see something cool, the next time out—perhaps even years later—you expect to see it where you did that very first time. My particular manifestation of this odd, nature-lover affliction is even worse. I often expect to see what I’ve seen before not only in the same tree, but perched on the very same limb.

Species themselves are partly to blame. Some exhibit, in the lingo of behaviorists, strong site fidelity, otherwise known as philopatry. Derived from the Greek, meaning “home-loving,” philopatric critters are loyal to localities. Some megapodes, or ground-laying birds, in Australia, for example, will reuse the very same mound for a nest every year, only abandoning it when calamity strikes or when it literally falls down around them. That’s breeding-site philopatry. Another form, natal philopatry, is living out your years where you were raised. This coming-back-to-our-roots is the form most of us can relate to. It also explains my fondness for a faithful pair of phoebes that chooses the same eave under my porch year after year. When this pair passes on, I’m confident their kids or grandkids will take over. They’re attached and so am I.

But nature is varied. Many other species refuse to don such straitjackets. When they’re not manacled to a nest or frantically feeding fledglings, they’re prone to wander widely. Others are even more nomadic, dyed-in-the-wool vagabonds—the human equivalent of our wanderlust friends that head west in their vintage Volkswagen camper vans. I understand all this. Even so, each day I drive home from work, I hopefully scan the same snag or ditch or fence post, hoping for the same owl or hawk or meadowlark that I saw once before. Rain or snow, if my friends aren’t where they’re supposed to be, I’m let down. But hope springs eternal and tomorrow I’ll scan the exact same places again.

Part of the problem is that the roots of this see-it-once-expect-to-see-it-again condition are buried in a spot that’s only accessible to a brain surgeon: the medial temporal lobe of my hippocampus. This vast neuronal network is the wardrobe in which our mental maps and memories are hung. When we revisit a place where we experienced something memorable—say, saw a great gray owl—the place cells in the hippocampus fire anew. As Jennifer Ackerman writes in The Genius of Birds, our memory of a thought is married to the place where it first happened.

This is why, I’m guessing, many birders I know are as philopatric as some of the species they search for. We birders pay attention. Consciously or not, we’re perpetually scanning: tree limbs, rooflines, hilltops. We study contours, scrutinize specks, and look for irregularity. Usually we find nothing. But occasionally, lightning strikes. And when it does, and that irregularity turns into a great gray owl, it’s satisfying in the same way that finding your lost car keys is, provided it’s in a spot you’ve already looked twelve times. Our well of memorable sightings deepens over time, and our connection to place—our place—grows stronger. Certainly the lure of watching bountiful birds in exotic locales is ever enticing. But my circle of birder friends agrees with Dorothy: there’s no place like home.

These feelings form, in the words of psychologist Ferdinando Fornaro and his Italian research team, a landscape identity. For Fornaro, this identity includes “a set of memories, conceptions, interpretations, and feelings related to a specific physical setting.” It goes like this: The more time we spend in an area, the stronger the bond. So all who live in a place for a while develop some sort of landscape identity, whether they like it or not. Seems pretty obvious. Less obvious, perhaps, is my contention that birders—and surely botanists, lepidopterists, and all stripes of nature lovers—form stronger landscape identities than others. Why? Because it’s not just the birds we grow fond of. The habitat that housed the birds—the swamps, brush piles, and power lines—becomes just as wonderful. Because of this, birders and other nature lovers can find beauty in places others can’t.

This is why I wasn’t too surprised when I saw a house advertised recently on an online birding listserv. It was near, but not on, Lake Ontario. Rather than lakefront with expansive views, this house was across the street, its view obstructed by other houses, fences, and hedges. “Great house and migratory stopover site,” the ad read. “Rarities not uncommon.” Despite the oxymoronic last line, the house undoubtedly lived up to its billing. Every spring and fall, songbirds, intimidated or exhausted by the Great Lake, probably dropped by in droves. The birds didn’t need waterfront and limitless views. They wanted brushy tangles, hedges, and swampy areas, places with food. The advertised house was one refined aesthetes with deep wallets would scoff at. Quite literally, it was a house for the birds. And since it was, the savvy house lister went after birders.

System administrators promptly removed the listing, which didn’t surprise me either. It was a site for listing birds, not houses. Regrettably, I wasn’t able to read the fine print before the ad was pulled. Perhaps it was just an opportunistic birder who needed to sell the house quickly. But I can’t help but hope on a deeper level that the house seller and I are the same species, one with a stronger-than-usual landscape identity, made even stronger by the great birds that we can’t keep ourselves from searching for.

RENOWNED ECOLOGIST Aldo Leopold once wrote: “Everybody knows that the autumn in the landscape in the northwoods is the land, plus a red maple, plus a ruffed grouse. In terms of conventional physics, the grouse represents only a millionth of either the mass or the energy of an acre. Yet, subtract the grouse and the whole thing is dead.” Leopold was writing about more than mere ecological equations. He was expounding on the importance of that slippery concept called value—subjective value of landscape—and the importance of cryptic little chicken-like birds. Granted, tourists will never flock to the northwoods to gape at coveys of grouse teetering about the underbrush. Leopold knew that. He also knew that grouse aren’t even vital for ensuring ecological function (helpful, yes, but not essential). He was after intrinsic value. That grouse are there, even if rarely glimpsed, is what counts.

I learned this lesson early and in an unexpected way. The movie Jaws played on our old, boxy TV in the family room. My nerve-wracked, eight-year-old frame was wedged between my two older siblings. Like millions of other viewers, I was terrified. Not whenever the great white appeared, but, rather, precisely when it didn’t. When it lurked below, John Williams’s infamous score launched me into apoplexy. Two-thirds of the film, the shark is submerged, shrouded in mystery.

It was a happy accident. Spielberg disliked the sharks he’d commissioned. They weren’t frightening enough. With time running out, he opted to keep his great white concealed. It was pragmatic, Hitchcockian, and genius. Jaws quickly became the highest grossing movie in US history, winning three Academy Awards and spawning musicals, theme park rides, and best-selling computer games. More importantly, it showed us all that the mere idea of a shark is more mesmerizing than the shark itself.

I’m convinced that birders, and most other nature enthusiasts for that matter, understand this idea. What we have trouble understanding, however, are attempts that scholars sometimes make to quantify such value. In 2016, Fornara and his cadre of researchers, the same folks who coined “landscape identity,” attempted to quantify the subjective value people have toward place. It was a simple experiment: Photographs of natal and foreign landscapes were placed in front of subjects who were then asked to evaluate their feelings of “self” in response. Unsurprisingly, photos of one’s native region tended to produce stronger emotions. Yes, the researchers dryly concluded, research lent some quantitative support to the theory of landscape identity.

Something about the act of objectifying subjective feelings just doesn’t sit right, however. In my graduate seminars, I well remember my distinguished professors cogently arguing about the need for attaching dollar signs to ecosystems and the services they freely render. As a professor myself, I’ve even assigned heavy-duty readings on the subject, like “Economic Reasons for Conserving Wild Nature,” which appeared in Science not too long ago. The logic is straightforward. Humanity benefits from nature. Such benefits should incentivize us to conserve it. But it doesn’t. The benefits we enjoy from ecosystems are difficult to commoditize, making them even more difficult to capture with conventional, market-based analysis. So humanity continues to convert habitat—a euphemism for destroying it—relentlessly.

My desire to affix price tags on the world’s ecosystems is tempered by the chilling words of Kenyan Nobel Peace Prize winner Wangari Maathai, who founded Kenya’s Greenbelt Movement. “If you can sell it,” Maathai wrote, “you can forget about protecting it.” She had witnessed a trend as Kenya transitioned from a colonial state to independence. Privatizing public land, or commoditizing it in any way, ended in habitat conversion and development. Landscape identities were converted in the process, some lost entirely. Yes, attaching dollar signs to nature is a two-edged sword. And in some places, it cuts both ways.

A FEW MONTHS AGO, I walked into an information kiosk for the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument in southern Oregon. The tiny kiosk appeared to be a converted tool shed. September sunlight streamed through the lone window as I browsed the displays. On my way out, a poster by the door caught my eye. “WHY YOU SHOULD CARE ABOUT BUTTERFLIES,” it proclaimed in big, block lettering. Underneath in smaller print were a host of services the butterflies provided, from pollination to pest control.

I commend the intentions of such poster makers. But it worries me too. Is it just another misguided attempt to put objective value on subjective, priceless things? More worrisome, of course, is that we need reasons to care in the first place. Native Americans certainly didn’t need reasons to care. Nor do they today. Recognizing that the land is the source of all sustenance, it has long been the de facto definer of identity, both tribally and individually. Leslie Marmon Silko, a Pueblo, suggests the term “landscape” is misleading, namely how it has entered the English language. A landscape is not a portion of territory the eye can comprehend in a single view. Nor does it correctly encompass the relationship between humans and their surroundings. Viewers are not outside or separate. Rather, Silke writes, “viewers are as much a part of the landscape as the boulders they stand on.” Likewise, Luther Standing Bear, Chief of the Oglala Sioux, saw precious little separation between humans and nature. “The American Indian is of the soil,” he wrote, “whether it be in the region of forests, plains, pueblos, or mesas. He fits into the landscape, for the hand that fashioned the continent also fashioned man for his surroundings. He belongs just as the buffalo belonged.”

Rather than spending my remaining days on earth trying to convince people to care, I prefer to teach this lesson—we’re all in this together. Caring may be irrelevant anyway. “It doesn’t matter whether people care or don’t care,” says science writer Elizabeth Kolbert. “What matters is that people change the world.” Placing ourselves in nature is critical. It’s the only way to recognize our reciprocal relationship. This is my rationale for spending my days immersing people in the natural world, be they my children, my students, and even my parents. Instead of trying to drum up reasons to care, I’ve decided to invest in forming landscape identities. It’s a small goal, but it seems more attainable. So I focus on birds, although butterflies and flowers work too. Birds are bountiful (for now at least), beautiful, and pretty easy to get attached to. With a little practice, one can figure out where to find them. Sometimes, of course, they come to us.

But on that afternoon drive in the mountains of southern Oregon, the owl we sought—the great gray—hadn’t come to us. Like always, I had irrationally expected it on the same limb as before. This owl obviously lived above the trammels of routine. Reluctantly, we said goodbye to the meadow and drove on. Thirty seconds later, however, I brought our car to a screeching halt. There, on a skinny fence post, just a stone’s throw away, was an impossibly large and regal bird. It was so obvious that even my skeptical son didn’t need to confirm it. The great gray owl swiveled its massive head and leered at us with lemon yellow eyes. We snapped photos, looked through binoculars, and just watched. It dawned on me then that we’d found much more than an owl. We’d found a point of attachment. We’d found, each in our own way, the start of a landscape identity.

I’ve never seen another great gray owl. Since I no longer live in the mountains of southern Oregon, it’s unlikely I ever will again. That’s okay. I know the sunny glades where they hunt and the shadowy haunts they retire to. I know they’re out there, hidden from human eyes. Perching. Pouncing. Priceless.

Eli J. Knapp

Eli J. Knapp, PhD, has had a fascination with wildlife ever since obsessively counting deer on his bus rides to school every morning as a kid. His wildlife interests have put him into kayaks, hot air balloons, dilapidated land rovers, and many pairs of hiking boots in search of new species and experiences. When not watching birds, Eli teaches courses in conservation biology, wildlife behavior, human ecology, and Swahili at Houghton College in western New York. His book, The Delightful Horror of Family Birding: Sharing Nature with the Next Generation, will be published by Torrey House Press in November 2018.