Nonfiction

FALL 2021Multiculturalism

by BENJAMIN DUBOW

“If you keep feeding [the sourdough] and maintaining a hospitable environment,

the culture . . . can persist for generations.” [1]

Definition 1: symbiosis refers to an “association of two different organisms . . . which live attached to each other, or one as a tenant of the other, and contribute to each other’s support. Also more widely, any intimate association of two or more different organisms, whether mutually beneficial or not.” (OED, 2.a)

I named my starter Orlando, after the titular character in Woolf’s novel. I got her from Arcade Bakery in Tribeca about two or three years ago—I just called them up one day and asked if they had a mother they might be willing to share, and they did.

The bakery is no longer there, but Orlando is alive and well. I feed him every morning; in return, they feed me—and my friends now, too, since Orlando and I have been collaborating on a sourdough challah recipe for the Shabbat dinners I’ve been hosting here in Ames.

Two vastly different forms of culture at play, they offer mutual support. It’s not a quid pro quo. The operative force is not expectation, but something else entirely.

“As a dynamic between two species, coevolution has been described as ‘an evolutionary [dialectic where each species responds to changes in the other]. Life, however, is never so simple as to be limited to just two interrelated species; coevolution is a complex and multivariable process through which all life is linked.”

Axiom 1: all cultures are inherently symbiotic.

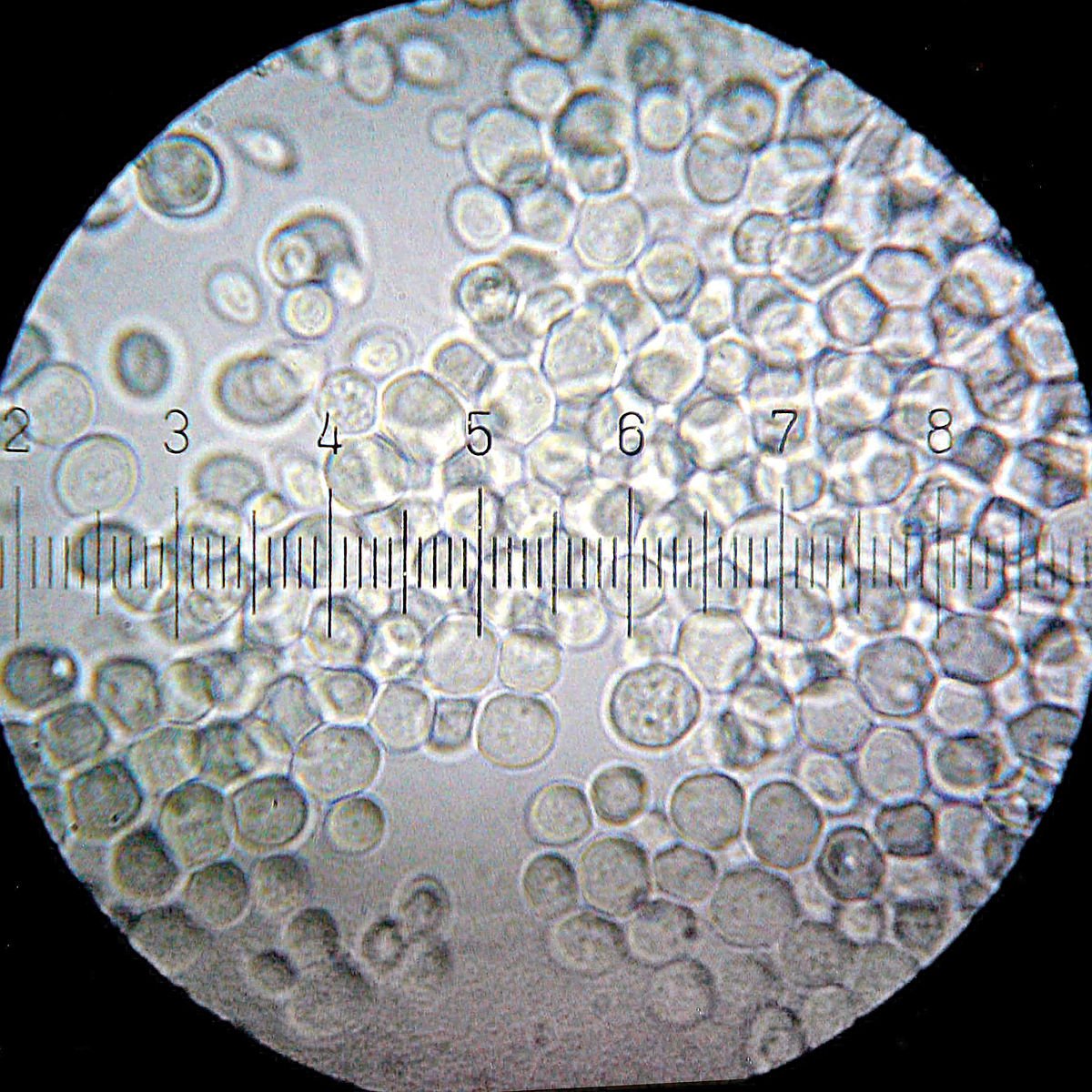

A sourdough starter, also referred to as a “mother,” is a symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast. These microorganisms have adapted to tolerate—and actually depend on—each other’s presence; the culture is not stable if lacking either.

Populations fluctuate over time. The shifting balance of Orlando’s many selves might best be described as a dynamic equilibrium. This, too, something Woolf would get.

Common strains of yeast (single-celled fungi) in sourdoughs are Saccharomyces cerevisiea, Kazachstania exiguus, K. humilis, K. exigua, and Hanensula anomala, though there are plenty others at play, too. The variety of different strains in varying proportions is part of what gives breads from differing locales their unique signatures, since specific yeasts thrive under specific conditions; like everything else, sourdough is largely a reflection of its environment.

E.g., a sourdough we made in Colorado two months ago tastes different than one we made right afterwards in New York; these are subtle differences, slight but telling variations on the themes of nuts, fruits, old books, and that haunting zest that even now makes me salivate. The point is, neither tastes exactly like the one Orlando and I make these days in Ames, Iowa.

Orlando’s alterations help me realize my own as I taste our new contours of being. Both of us changelings, inflections of nuance refracted through place. There are adjustments, of course, not all of which are immediately comfortable, and it can take time to find patterns that feel good and right.

That challah I mentioned, for instance. I didn’t regularly bake challah at home, nor, really, did anyone in my family. We didn’t need to, since there are plenty of excellent Jewish bakeries in New York to supply our weekly Sabbath bread. But here, in Ames, where Jews are few and far between and, for the first time in my life, I have to actively fan the flame of my tradition if I want to feel its warmth, baking challah with Orlando has become a way to connect to this part of myself—a way to keep my culture alive.

“Who exactly is the servant of who? [2] Are the acidifying bacteria in milk or the yeasts in grape juice our servants,

or are we doing their bidding by creating the specialized environments in which they can proliferate so wildly?

We must stop thinking in hierarchical terms and recognize that we, like all creation,

are participants in infinitely interrelated biological feedback loops,

simultaneously unfolding a vast multiplicity of interdependent evolutionary narratives.”

Definition 2: mutualism refers to a symbiosis “between two [or more] organisms of different species which contribute mutually to each other’s well-being.” (OED, 2.a)

If I had to describe our relationship in terms of an equation, it would be: x = πr2, where the variable r is understood to mean respect.

Respect squared is just another way of saying respect • respect, which is just another way of saying reciprocity. That is, r2 = reciprocity.

And π = the universal ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter; a constant.

And x, of course, means kisses. Kisses are just another way of saying, “love.”

Therefore, love = that which defines a circle • reciprocity. Q.E.D.

“We must build community not only with people, but by restoring our broad web of coevolved relationships.

The practice of fermentation gives us the opportunity to get to know and work

with a range of microorganisms with which we have already coevolved.”

Postulate: place-specific (from the Latin specificus, from the Latin for “species”) symbioses are the defining feature of any given culture.

We commonly assume that yeasts are the main event in bread. In sourdough, however, they are in fact far outnumbered by the lactic acid bacteria (LAB). In a mature starter, the LAB:yeast ratio is around 100:1.

(Still, we have this tendency to think first and foremost of the yeast.)

Aside from the diversity of yeast strains, the presence and diversity of strains of LAB in the starter is the distinguishing characteristic of sourdough breads. They, too, vary widely, and depend on the local environment: temperature, humidity, quality of light, quality of air, hardness of water, the character of local soil and the flora that flourish there—in this exquisitely sensitive web of relations, every factor configures.

The most common LAB genus in sourdoughs is Lactobacillus, of which we recognize over two hundred “distinct” species; other commonly found genera include Leuconostoc, Pediococcus, Enterococcus, Streptococcus, Weissella, and Lactococcus.

“Distinct” because species distinctions can get tricky in the prokaryotic world, as their bodies are capable of horizontal gene transfer across species lines, which increasingly look less and less, strictly speaking, line-like.

“Fermentation is more dynamic and variable than cooking, for we are collaborating with other living beings.”

Hypothesis: mutualistic cultures are the most fruitful.

To start making a loaf of bread, I first mix flour and water together to make what’s called an autolyse. Then, I grab a healthy scoop of Orlando, voluptuous and pregnant with life, and add it to the mix. I like to use 18 percent starter relative to flour weight for symbolic reasons: in my culture, 18 signifies chai: “to live.” Not incidentally, the word for bread in Egyptian Arabic is aish, which also means life. (Note that the noun form of chai—chaim—is plural. This seems crucial.)

Salt comes a little bit later, to give them all time to acclimate.

Orlando, I think, is happy to give this part of herself to the cause. They are infinitely regenerative, after all, and are soon fed and so renewed.

Thus secure in the knowledge he’ll live on, I put the loaf into a 500º oven.

When the bread comes out thirty-six minutes later, the center is still cooking. I like to bend over and, ear a breath away from ear, listen to the quiet crackle.

Technically, this is the sound of the brittle crust contracting.

Orlando and I, though, we recognize our song’s refrain.

[1] Unless otherwise noted, all quotations are drawn from The Art of Fermentation by Sandor Katz (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2012).

[2] I was sorely tempted to [sic] this apparently erroneous use of the subject form, but then I remembered my purpose here.

Benjamin DuBow

Benjamin DuBow is a writer, traveler, and award-winning chef; in all three of these, he’s interested in how things relate to other things, of being-in-relation. Benjamin has a BA in English from Columbia University and currently lives in Ames, Iowa, where he’s pursuing an MFA in creative writing and environment at Iowa State University.