Nonfiction

SPRING 2024Reading Palms

Words and Images by JOLIE KAYTES

On a recent trip home to Florida, I read palms: sabal, red leaf, bottle, areca, Alexander, royal, wax, and coconut. It is my first visit back since the hurricane two months ago. I walk the beach, bike the roads. Damaged domestic stuff and tree debris stack up all over. The palms, however, thrive. With their riotous, wispy, tousled sprays of feathery and fanning fronds, their flexible trunks, and their seemingly unstable proportions, the palms held strong through the storm, endured the winds, sandblasts, salt, and surge.

The word “palm” refers to the inner surface of the hand between the wrist and fingers and, of course, to the plants, which are named for their leaves’ likeness to a spread hand. We may have our palms read—their shape, size, and the crisscross of crinkles imprinting them—to learn something about our futures, to ponder possibilities of the heart and mind. An ancient psychic art practiced across cultures, palm reading, or palmistry, has been perennially embraced and forbidden, considered both a route and a ruse to try to discover our destinies.

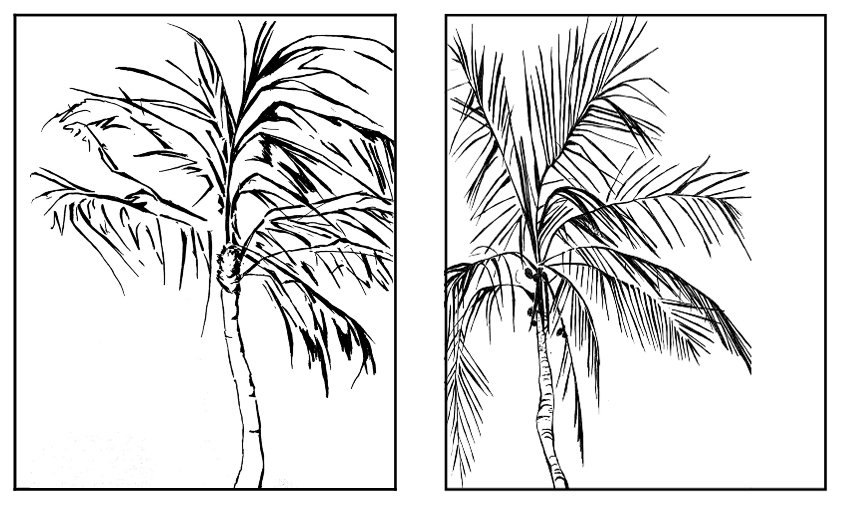

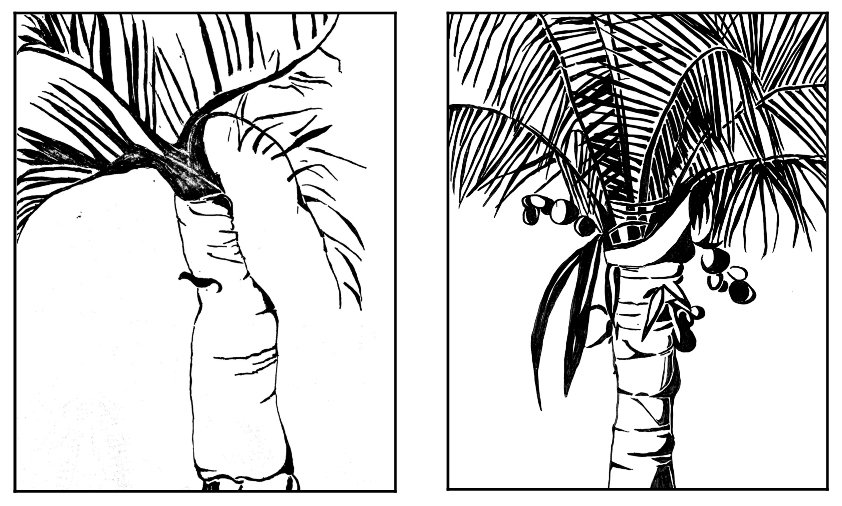

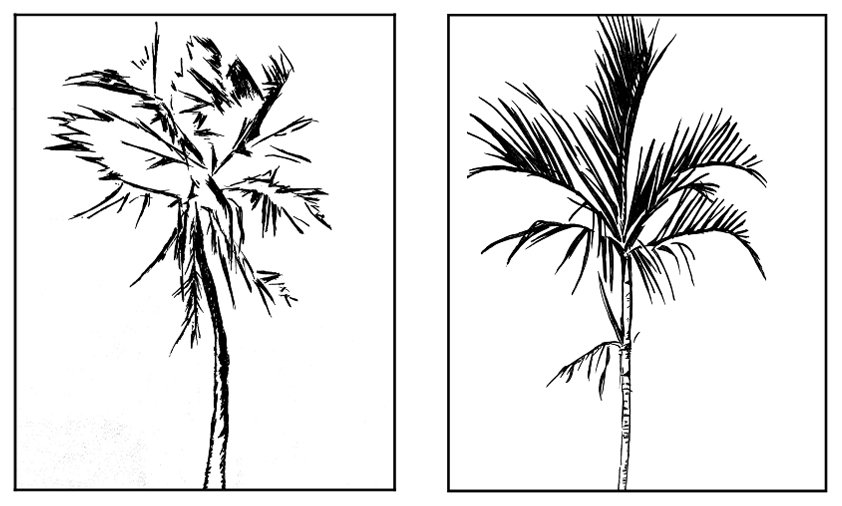

I’ve drawn palm trees for most of my life. When I draw them, I start as I do with most sketches: I gaze out, widen my eyes, and take in. Without peeking at my paper I make marks, intent to record energies. I ink all over the sheet. From body to pen to page, the marks become the bones.

In the beginning phase of a drawing, I attune to my senses, focus on a palm’s essence and context rather than the form. While sketching, I might absorb a blur of birdcall, take in the jasmined air, or be enthralled by anoles trolling the screened enclosure. I am unconcerned with what fills the page; rather, this initial witnessing with pen situates me.

My opening gestures seed the composition, though after these first lines, I look and assess. I’m interested less in the literal, more about feeling. Sometimes, if something seems off, I look out again, add more. Once I’m satisfied with the skeleton of swoops and dashes, I intensify and grow out the vegetation. I’m still in exchange with the plant, though now I see, engage, and build the drawing.

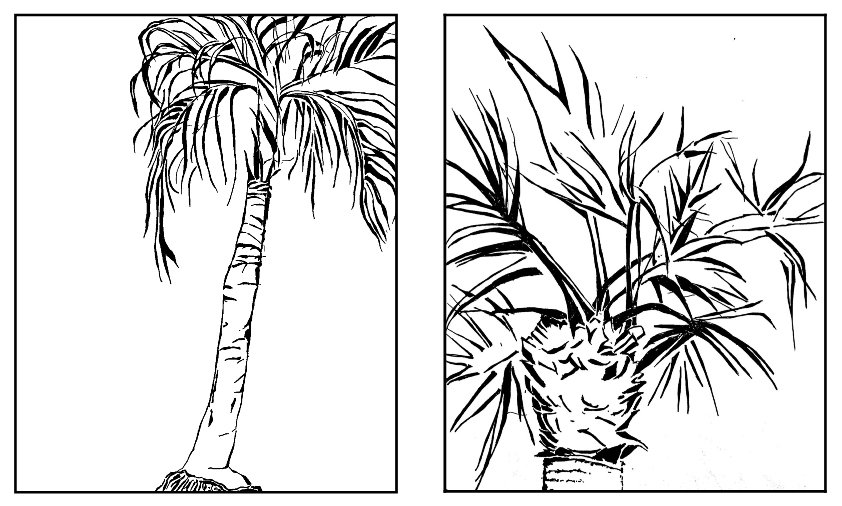

Though they are icons of gentle breezes, whimsy, and ease, palms possess strength comparable to reinforced concrete. Caress the bottoms of many species, say, royal palm, and note they are hard and cool like an old park bench. Other varieties, such as Bismarckia, are reminiscent of organized strand board, appearing soft, yet feeling surprisingly solid, durable, and slightly rough to touch.

Botanically, palms are more akin to grasses than trees. Cut through the trunk and rather than rings, find a densely stippled surface that is woody but, technically, not wood. Further rendering palms untreelike: their solitary, instead of double, seed leaf; their fibrous rather than tap roots; their parallel versus branching venation; and their odd-numbered as opposed to even-numbered flower parts.

I understand and appreciate these biological distinctions, and I also experience palms as trees: long-lived, life-giving, reliable companions with upright trunks and a complex crown of foliage, knowledge keepers, magic makers, and repositories of potential.

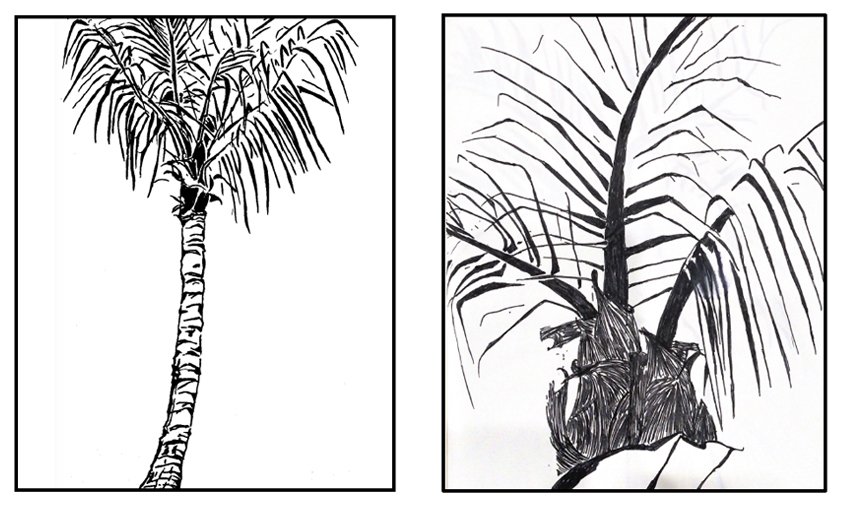

As I draw palms, I marvel at how the fronds, which I know to be heavy when they are grounded, retain and release light, become fractalled portals into the blue. How, up close and from afar, the fronds float, disembodied from the trunk, illusory, fleeting. Amid their sunlit ruffle, like shimmery paper shuffled by breath, I beam.

From the outset, I draw with black permanent marker, no penciling or erasing. For me, this activates the drawing, discourages preconception, and motivates detachment. What goes on the page stays on the page, and every sheet becomes a souvenir of strokes, holding the strata of observation, instinct, and impulse—each picture truly an inkling borne from palms, pen, and the moment.

The drawings I learned to make in design school provide information about a future condition—the design’s material qualities, construction details, spatial dimensions, overall organization. Though it was satisfying to craft precise and measured plans, sections, and elevations, I consistently preferred to stay in the mess of process sketches, to ideate with the scratchy, scruffy, blobby images that were “not to scale” yet vividly expressed an aspect of the design or its promise.

When I draw plants now, particularly palms, I reconsider and reimagine rules instilled by past instructors. I suspend what I know of reality, about gravity, logical connections, the physics of what bears weight, what keeps a tree upright. It is a conscious—and generally blissful—effort of unthinking. If I draw what I know, the tree becomes a caricature or “cartoony,” as a former teacher said. Of course, palms are the ultimate cartoons: woody sticks festooned with a poof.

Living in Florida—which equates to living within fragile wetlands, atop limestone bedrock, on exposed coastlines—also requires suspending reality, though the denial comes with catastrophic consequences. Post storm, the beachfronts, bayshores, and inland neighborhoods are collages of broken structures and their remnants: boarded window frames, capsized stairs, deformed railings, toppled balconies, destroyed appliances, sodden furniture, mangled foundations. The hurricane revealed the built environment’s vulnerabilities and the fallacy of our choices, our delusion. And yet, rebuilding and new construction in Florida, before and after the hurricane, are on, big-time.

Occasionally, when I am feeling snarky, I make up names for the development-driven garden styles of South Florida: The Subtropical Suburban, Dutch Colonial Holiday, The Pirated Caribbean, Pink Splashes, The Versailles Variations. The region’s observable obsessions with youth, beauty, plastic surgery, contained curves, and exaggerated body parts are mirrored in its designed landscapes. Here is the basic design scheme and maintenance plan: monochromatic, kept-low lawn, flanked by multilevel, coiffed, and thickly leaved hedges, bejeweled with a mature tropical tree such as a tangly banyan or a showy specimen palm, allowed to explode, unfurl, sprawl just so, teetering on, though ultimately groomed, out of control.

I appreciate the rehashed mash-up of landscape design traditions. I find humor in the (clueless?) co-opting of forms originally intended to denote power, elicit awe, convey cosmic knowledge, and I willingly tolerate designs inspired by (appropriated from?) working, agrarian environments. Though I am saddened and troubled that these input-intensive, vegetated exteriors frequently function as passive backdrops, what needles me most existentially is their freakishly speedy installation—from bare ground to mature, fully flourishing, gushing gardens in a few days—and how it falsely suggests a long engagement and intimacy with place.

Palm, as a verb, generally means to conceal, deceptively so. The expressions “palm off,” “itchy palm,” “in the palm of someone’s hands,” “grease someone’s palm” all get at this darker definition related to taking and manipulating, and reflect an aspect of humanity that knowingly tricks.

Florida’s instant landscapes (just add water!) distort seasonal scales and deny the drawl of time. They are pretenses that distance us from cycles, distracting us from the messages held by plants, animals, and weather. They are a dangerous sleight of hand.

On the stretch of beach I run, the sand and sky sandwich a sea vibrant with sparkles. There are signs posted at every access point warning, “Caution! Stormwater and Hurricane Debris in Water.” People saunter barefoot and swim, presumably unfazed. Plovers, pipers, and willets zigzag where surf licks shore. Just above the wet zone, terns and gulls stand en masse, sentinels facing wind. Children charge at them as their parents and passersby watch idly.

Above the high tide line, between swaths of dune vegetation—sea oats, sea grapes, sunflowers, railroad vine—it is hard to discern demolition from construction. If I squint and block out the tower cranes and the remains of condos and mansions, the palms—big, little, scrawny, tall—dominate and become the visual sinew binding the scene together.

The palms’ bounce-back capacities tickle, but also prickle me. I wonder if the plants’ resilience misleads, providing a kind of permission for humans to “rinse and repeat” regardless of impact, to steal from the future.

An adept palmist holds your hand and a space for meaningful exchange. As with making a drawing, a reader allows flow, interprets lines, and finds connections. Though they are usually framed—with skepticism—as oldfangled fortune-telling, I like to consider palm readings as offerings about the body, chance, and circumstance, informed by deep looking, touch, and care.

At dusk I amble across a former and semi-feral golf course near my mother’s house. The once-manicured putting green is a patchy shag of olive, lime, and pea, writhing with ants. The water hazards quiver with the dance, prance, and pluck of ducks, herons, anhingas, egrets, gallinules, storks, ibis, osprey, and the occasional pelican or eagle. Free from cleats, clubs, carts, and balls, the birds feast, preen, and linger, seemingly unflappable, despite themselves.

I love being on the old fairway to take in the ruins of leisure alongside the glimmers of a liberated landscape, to feel the terrain tingle with the loss, renewal, and persistence of process.

The palms here have withstood the hurricane and neglect. Their fallen fruits birth shoots; their fronds, aloft, effulgent, streak the sky. Rooting and rising, they gracefully embody the tensions of time and place, rousing me to read and dream the landscape anew.

Jolie Kaytes

Jolie Kaytes is a professor of landscape architecture at Washington State University. She spent her formative years in South Florida, where she wandered along shorelines, slogged through sloughs, and frolicked among subtropical flora and fauna. She currently lives in Moscow, Idaho, and is working on a book about reimagining invasive plants.