Fiction

SPRING 2024The Miracle Tree

by MARK BRAZAITIS

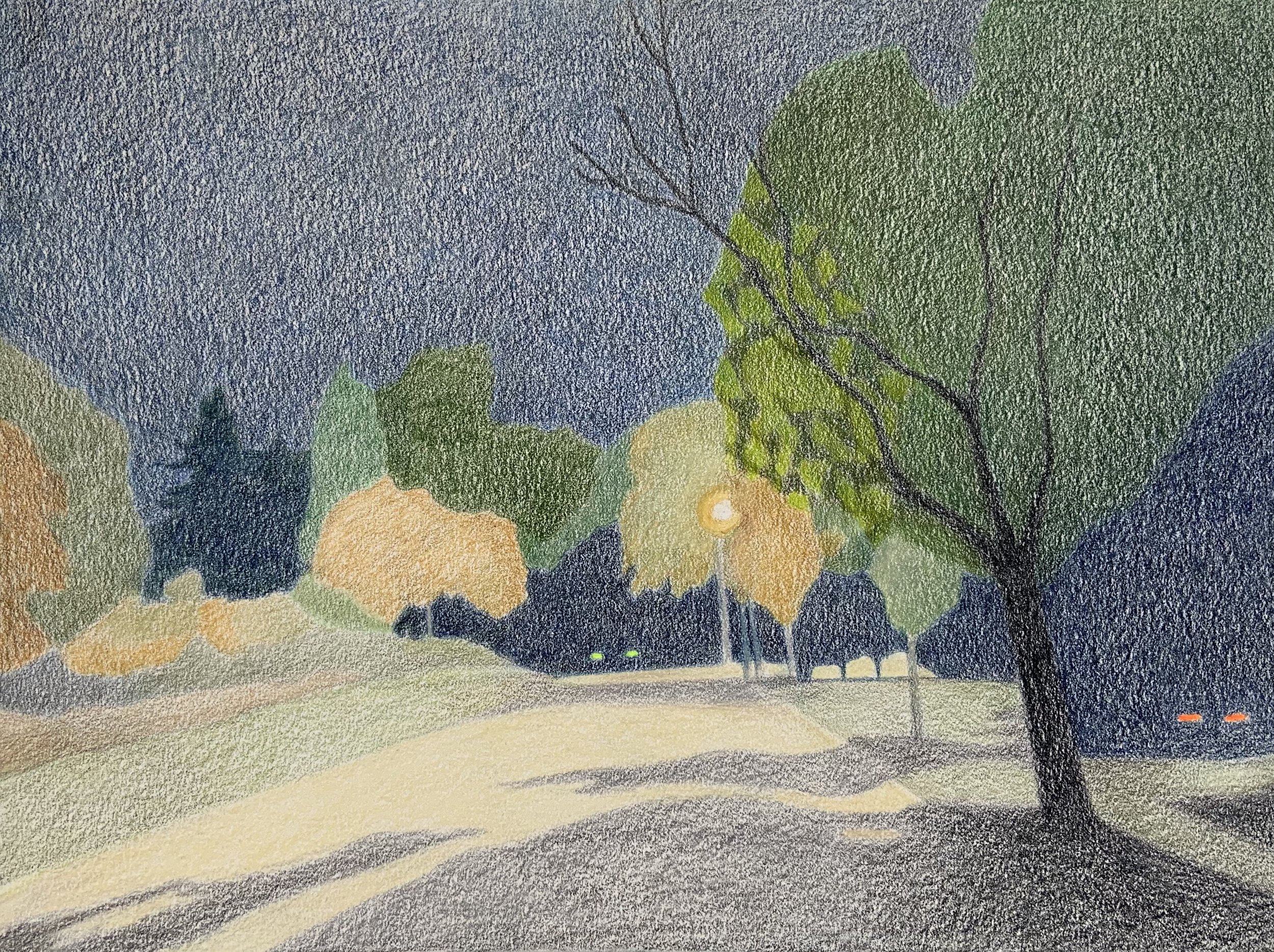

Our tree stood in a field at the farthest point from the only entrance to our neighborhood, which was called a circle but looked like a teardrop. Our neighbor Teresa Markovitch, an amateur arborist, identified our tree as a red maple, but we had doubts. Yes, its leaves looked red at times. But depending on the sunlight or the moonlight, they also looked pink or purple or silver. In the brightest light, they were translucent. Our tree was close to one hundred feet tall, and its four bottommost branches extended at least twenty feet from its trunk.

As far as we knew, the half-acre of land our tree grew on didn’t belong to anyone. A handful of us took turns mowing its grass every couple of weeks. We held the neighborhood’s annual picnic on it, sitting on lawn chairs and eating potluck casserole and fruit salad in the shade our tree provided. Martha Rothstein conducted yoga classes under its branches. Children climbed our tree in the summer and built snow forts around it in the winter. For Lydia Little, a retired kindergarten teacher and poet, our tree was a muse.

We didn’t think of our tree as anything special until Rose Andrews’s TikTok video.

Rose, a high school junior who lived near the entrance of our street, played shortstop on her school’s softball team. During the second game of the season, as she was rounding first base after hitting what she hoped would be a triple, she felt her right ankle crack. She fell to the ground screaming.

Rose’s doctor told her she would need six months to recover. Although she despaired at missing the rest of the softball season, there was nothing she could do except mope in her bedroom, write melancholic posts on social media, and hobble around her school’s hallways.

One Saturday afternoon, a week after she’d injured her ankle, she limped out of her house and down the street. She soon found herself standing in front of our tree. “I don’t know why, but I talked to it,” she told her TikTok audience. “I spoke about my injury and how sad I was because I couldn’t play softball. A minute later, I began to feel better. Five minutes later, I wanted to jump into the air, so I did. When I landed, I felt no pain at all.”

On Monday, she rejoined her softball team, slugging a home run to help the Leopards beat the Coyotes, their crosstown rival. In a second TikTok video, she interspersed images of her rounding the bases with images of what she was calling the Miracle Tree.

We didn’t disbelieve Rose. We could see she was healed. But we didn’t believe her injury had ever been as serious as she’d said. “It was probably no more than a twisted ankle,” one of us declared at a cookout next to our tree. “Kids exaggerate.” Jokingly, we made a toast to our miraculous tree.

If Rose had been our tree’s singular medical success story, our lives might have remained unchanged. But people in town who’d lost faith in traditional medicine sought cures from our tree, and two early success stories gilded its reputation as a healer.

Milton Escobar was the longtime head chef at the Daily Diner, which, in defiance of its name, was closed on Mondays. Two years earlier, a fire had erupted in the diner’s kitchen. In escaping the blaze, Milton suffered third-degree burns on half of his face. He’d been to several burn specialists and several plastic surgeons, but none had restored his face to his satisfaction.

One Monday morning, Milton drove to the field where our tree stood. Ever since the fire, he’d consoled himself by thinking his burns were God’s way of testing his faith. If praying to our tree was a form of paganism, he was evidently willing to be a heretic.

When he next saw himself in a mirror, he thought he was hallucinating, but his wife verified his transformation with cries of wonder and tears of gratitude.

As with Rose, we didn’t exactly disbelieve Milton’s story. But we suspected he’d skipped a detail in his recitation of events. A treatment prescribed by one of his burn specialists or plastic surgeons must have at last succeeded. Or his burns had healed naturally, and he’d only noticed the transformation after he visited our tree. Whatever the true cause of his restoration, Rose filmed a triumphant video of Milton. “Nothing healed me,” Milton declared to Rose’s growing TikTok audience, “until I visited the Miracle Tree.”

Third to be healed was Marilyn Bates, the former principal of the largest elementary school in town. Suffering from a recurrence of her breast cancer and unwilling to submit to more rounds of brutal radiation and chemotherapy, she rose from her bed one night and drove to our tree. Flinging her arms around its trunk, she exhorted, “Help me, please.” Our tree, she said, hugged her back. After their ten-minute embrace, she knew her cancer was gone.

Rose’s video of Marilyn, viewed more than 48 million times, sparked a pilgrimage to our tree of people from as close as the next county and as far away as Bangladesh.

Seeing the influx of visitors as an opportunity, Peter Snodgrass, our neighborhood association president, decided we should charge admission. There were mild objections, some based on our lingering skepticism about whether our tree was a miracle healer or a social media hoax, some based on doubts about who owned the land our tree stood on. “A tree owns itself,” declared Lydia Little, who objected to charging people for a cure no one had invented.

Everyone in our neighborhood, however, had financial exigencies, great and small. Mickey Magruder needed an artificial knee; Doris Pope’s twins had been accepted to prestigious private colleges but had received less-than-generous financial aid packages; Scott Smith’s house was overdue for a new roof. For his part, Peter Snodgrass was recovering from a gambling addiction and wanted to replenish the retirement account he’d plundered. By a 6-1 vote, we decided to sell $20 admission tickets to our tree.

We built a crude wooden fence around our tree and opened what would become a twenty-four-hour ticket booth.

The line of people eventually extended to the Sky River, more than two miles from our tree. When hotel rooms in our town became scarce, a dozen homeowners in our neighborhood opened Airbnbs. Dolly McAdams sold T-shirts, caps, and coffee mugs featuring our tree’s image. Her husband, Bob, cooked Oscar Mayer wieners garnished with leaves from our tree and advertised them as Healing Hotdogs.

When Peter unilaterally raised the admission fee to $100, we worried we would see a steep decline in pilgrims, but the number of visitors only increased. We were grateful for Peter’s business savvy until one day, more than a month after we’d opened our tree to the paying public, our neighborhood association treasurer, Mariah Colebank, presented us with a statement from our bank. Peter had deposited a mere $2,200 into our account.

Three of us volunteered to confront Peter about the situation. But when we showed up at his house, no one was home. The same proved true the following day and the day after. On the fourth day, his daughter, home on a break from college, told us that her parents were on an extended trip to Las Vegas.

Although Rose continued to feature success stories on her social media platforms—by now, she’d amassed more followers than the Pope—skeptics filled the Internet with their doubts, and a story in The New York Times quoted a dozen people who’d come to our tree expecting to be healed of various ailments only to leave with no change in their conditions. A young woman with the social media handle @TheBloomisOff, clearly a dig at Rose, posted interviews with pilgrims who’d traveled hundreds of miles and spent thousands of dollars only to discover themselves in the presence of #ordinarytree. Even more damning, she revealed that Marilyn Bates’s cancer went into remission almost certainly because of her heretofore undisclosed immunotherapy and not because of the so-called Miracle Tree.

The end of the public’s fascination with our tree seemed near. Quoting Robert Frost, Lydia Little, our poet, remarked, “Nothing gold can stay.”

But gold was on someone’s mind. Enter, the cowboy.

Orville Hayes might have been seventy. He might have been a hundred. His face was wrinkled like an ancient apple. He wore a black cowboy hat and black cowboy boots. The rest of his outfit was also black, in honor, he said, of a misunderstood and maligned natural resource: oil. He was from Texas, he told us, but he used to live in our town. He still owned a piece of it, he said.

Specifically, he declared, he owned the land where our tree stood.

He’d come back to town to claim what was his. He wasn’t the first person to do so. But he was the only person who presented us with a deed. He unfolded it against the trunk of our tree. “You’ll excuse me,” he announced to the handful of neighbors who’d gathered around him, “but you’ll have to skedaddle.” Facing the line of visitors, he shouted, “As for the rest of you, it’ll now cost you 250 smackers to visit this here arboreous wonder.”

We weren’t going anywhere. We claimed fraud. We claimed squatters’ rights. We claimed eminent domain. We called the police. So did Orville. We sued Orville. And Orville sued us.

Until the cases could be settled, the courts ruled, our tree would be placed in the custody of the state. The state replaced our modest wooden fence with a ten-foot-tall barbed-wire fence. No one was permitted to touch our tree.

Desperate to cure their ailments, however, pilgrims wielding wire cutters and grim determination climbed the fence. Some would-be visitors bought shovels and commenced digging a tunnel under it. Three pilgrims collaborated on building a bomb and blew open a fifteen-foot-wide section. Chaos followed.

To restore order, police used tear gas and rubber bullets. Thirty-two pilgrims and six officers were hospitalized.

In the aftermath, our tree was unrecognizable. Half a dozen of its branches had been broken off. It had lost an incalculable number of leaves. Much of its bark had been stripped. Its trunk and several of its remaining branches had been hacked and even bitten.

Believing the tree was dead, Orville Hayes renounced his claim. His gesture proved moot. A local reporter discovered that, years earlier, the cowboy had signed the land our tree grew on over to the county in lieu of taxes he owed on his pawn shop, Orville’s Stash and Dash.

Our tree’s reputation as the arboreal equivalent of snake oil by now overshadowed its renown as a miraculous curer of ills, and the number of pilgrims dwindled to zero. Even Rose Andrews had given up touting our tree’s healing powers and had turned her TikTok talents to other subjects. Her cat videos proved wildly popular.

We didn’t think our tree would survive the winter. The damage it had sustained seemed too profound. Once beautiful with sturdy branches, radiant leaves, and a symmetrical shape akin to a Christmas tree’s, it was now like a starving sailor on a desert island.

Spring arrived, and while our tree was, in a minor miracle, still alive, we stopped having picnics in the field where it stood. We allowed the grass to grow around it. Martha Rothstein moved her yoga classes to a studio downtown. With no pressing business and a lackluster bank account—Peter Snodgrass never returned from Las Vegas—our neighborhood association rarely met. Our tree receded from our lives like a dream.

Seasons passed, and we all but forgot about our tree. All but one of us. Or all save Lydia Little and an incalculable number of other living beings.

Lydia visits our tree in all seasons and all kinds of weather. Occasionally, one of her neighbors driving past it will give her a wave. One morning, as Lydia stood beside our tree in a light spring rain, Teresa Markovitch stopped her Toyota Sequoia (she’d bought the SUV with what she’d earned as an Airbnb host during the Miracle Tree’s heyday), rolled down her window, and said, “Do you need a ride somewhere, Lydia? You seem lost.”

“I’m right where I want to be,” Lydia replied.

“Writing a poem?”

“The poem is writing itself.”

At first, she always brought a notebook and pen on her visits to our tree. Long prepared to write an elegy, she was happy to write odes instead. Eventually, she left her writing tools at home. It’s poetry enough, she believes, simply to be one of the many lives the tree attracts and sustains. Cardinals. Blue jays. Hooded warblers. Squirrels. Rabbits. Daddy longlegs. Giant bark aphids. Two-lined spittle bugs. Caterpillars. Mosses in a dozen shades of green.

If weather permits, Lydia will lie under the tree and stare up at its branches, which stretch like long, balancing arms. She admires its intricate and accommodating architecture—here, a robin’s nest; there, a perch upon which a trio of American crows sits, waiting to taunt one of the neighborhood cats. She enjoys its cool shade and the artistic shadows it casts on the grass. She marvels at the way it extends toward the sky and welcomes, in silent communion, the sun’s rich, astonishing light.

Mark Brazaitis

Mark Brazaitis is the author of eight books, including The River of Lost Voices: Stories from Guatemala, winner of the 1998 Iowa Short Fiction Award, and The Incurables: Stories, winner of the 2012 Richard Sullivan Prize and the 2013 Devil’s Kitchen Reading Award in Prose. His stories, essays, and poems have appeared in The Sun, Ploughshares, Michigan Quarterly Review, Witness, Guernica, Under the Sun, Beloit Fiction Journal, Poetry East, USA Today, and elsewhere. A former Peace Corps Volunteer and technical trainer, he is a professor of English at West Virginia University, where he directs the Creative Writing Program and the West Virginia Writers’ Workshop.