THE HOPPER POETRY PRIZE

AUGUST 2019We are pleased to announce that Natalie Homer has received honorable mention for The Hopper Poetry Prize for her manuscript Under the Broom Tree.

“Going home always felt like defeat,” says the narrator of Under the Broom Tree. In this collection, a card sent from the grandmother opens to a “shrunken” past, a place once “full of treasure,” somewhere between fairy tale and dream. Time and man have changed the landscape—the “magic is gone . . . [the] enchanted forest of my memory turned sodden, tepid” and “smells seep into everything: the acrid reek of a lumbermill, the dairy farms, mildew . . .” From here, the poems set out for far-flung places, the journey into wilderness the trope. They roam from “turbines in a ragged line, twirling their white batons” to “sagebrush and horses and long-dead dogs.” They traverse the country from the Bannock Range in Idaho that “filled my windshield every day” to a “coal-bled” bridge into Ohio. They map an “uncomfortable going in / and again, coming out”— the “[d]riving past” the “ritual.” “I could never live here,” at one point the narrator says, though along the way, the places, the people that inhabit them, are “miss[ed] . . . before [they’re] gone.”

—Kathleen Hellen, author of Umberto’s Night

Natalie Homer received an MFA from West Virginia University. Her poems have been published in The Cincinnati Review, Meridian, Blue Earth Review, The Journal, Berkeley Poetry Review, and others. She lives in southwestern Pennsylvania. Enjoy a poem from Under the Broom Tree below.Under the Broom Tree

1 Kings 19:4–8

Sister, do you remember those cloth dolls,

goldenrod and cornflower, yarn hair, happy freckles?

The ones we found in the cupboard under the stairs?

We were friends, then, and I followed you

outside, carrying plastic dishes, a wooden high chair,

painted storybook bears fading from the backrest.

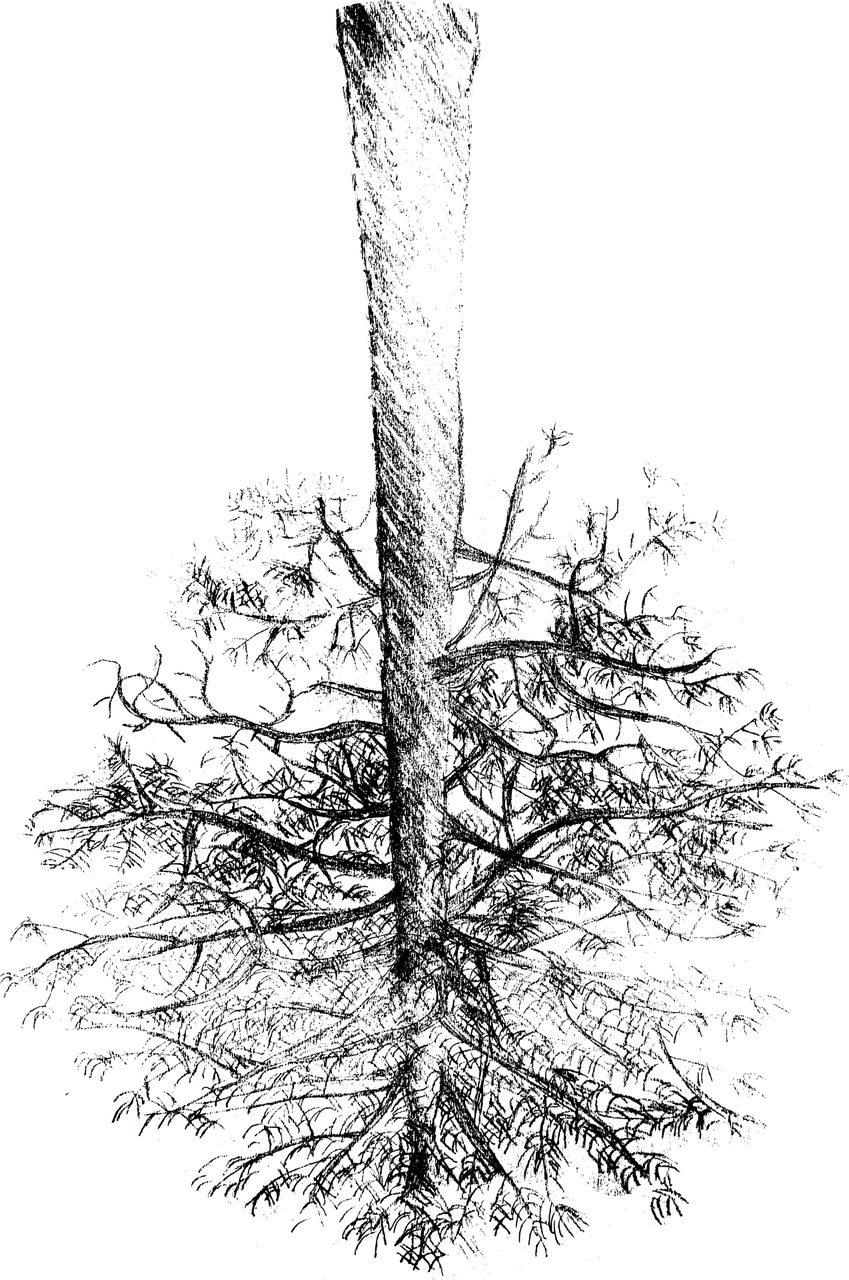

We called the Lodgepole Pine a broom tree

for its brushy branches that we broke off

and used to sweep the dirt in our little estate,

our play house in the Idaho mountains.

A smooth stone, baked in the sun, became a golden loaf,

we spooned sap as honey,

and sagebrush in water made the accompanying soup.

We were not weary then,

and we knew nothing of Elijah

and little of God for that matter.

Our coals and stones, bread and water

were our own, and surely no miracle.

Wildflowers put on their usual pageant.

We pressed Indian Paintbrush to our cheeks and lips,

believing the petals’ pigment would transfer.

You have always glowed golden and peach

and I was jealous of you even then—

of your long blonde braids and your slender hands.

Much had changed by the time, years later, I sat alone

in my windowless basement bedroom, the carpet ripped out,

the whole house made skeletal and echoing.

Outside, the wind sang its strange, sad howl

and swept snow across the road in milky tendrils.

I prayed for a convenient death

while you were upstairs, laughing your golden bell laugh.

I miss you, sister—

who you used to be, who I used to be

when we wove ourselves together without thought

so few years ago.