HEIRLOOMS

OCTOBER 2016

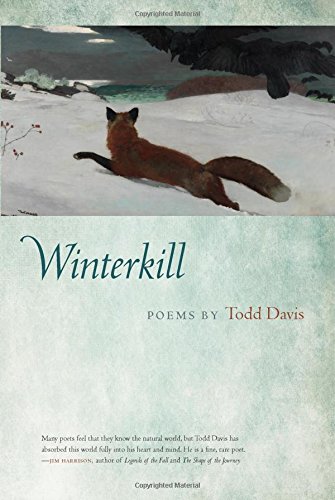

The late poet and novelist Jim Harrison (1937-2016) once said: "Poetry, at its best, is the language your soul would speak, if you could teach your soul to speak." He might easily have been talking about Todd Davis, whose latest collection, Winterkill (2016), reads like sacred text. Trafficking in the speech of what we might call the soul or spirit, Davis invokes those writers whose work traditionally embodies the spiritual-ecstatic (he quotes from Whitman, Levertov, and Tu Fu, to name just a few), while rendering scenes from the natural world and ordinary life with a transcendent tenderness and clarity. In his latest collection, the poems trouble the long-held assumption that we humans were meant to dominate and control the natural world. As he writes in "After Reading Han Shan":

Hearing crows talk, I've come to accept their intelligence rivals ours.

They remember the architecture of human faces even longer.

Any reader who spends time with Davis's wonderful work will see that his project centers on the act of present-moment observation. His poems often unfold as litanies of what he sees on a hike near his home, or while fishing and hunting, and Davis wisely leaves it to his readers to assemble these images and scenes into a greater whole. He goes on in the above-mentioned poem:

As I walk this path, I remember Han Shan wrote poems on rocks,

and trees, the parchment of cliffs. Some say he vanished

into a crevice in the mountain. In the ravine that divides

the mountains I live between, porcupine and bear disappear

behind rock outcroppings, and from bluffs at day's end

coyotes scream their thanks.

The world he describes, and which we all inhabit, is a brutal one, Davis reminds us. No matter how we scrawl our "poems on rocks" as if to mark our territory, we too will someday disappear "into a crevice." At the heart of many of these poems is an undeniable grief, not just for the incremental loss of the environment as we know it, but also for the father Davis remembers in several places, including the lovely elegy, "The Last Time My Mother Lay Down with My Father." In that poem, he wonders:

How did he touch my mother's body

once he knew he was dying? Woods white

with Juneberry and the question of how

to kiss the perishing world, where to place

his arms and accept the gentle washing

of the flesh.

Davis's poems, with their juxtaposition of the human-made and natural worlds, seek a kind of "acceptance" of the transience of all living things. He seems always to be looking for ways "to kiss the perishing world," and honor those plants and animals that may not be on this planet in their present form, or at all, for very much longer. This elegiac yet celebratory impulse takes on greater weight when he describes his own family's joys and losses, though many of these poems argue that, if we pay deep attention, nature can instruct and reflect our lives. After his father has passed, for instance, Davis continues to find reminders of him all around. In "How Animals Forgive Us," he confesses:

In the mountains above our house more than

twenty bear die each year. I refuse to hunt them

because when they rise up on hind legs

I see my dead father walking toward me,

and who wants to taste the meat that ushers in

such bitter dreams?

In this case, it might be considered a mercy, and it might make more logical sense, to hunt the bear that will die off anyway and give them a kind of "second life," as nourishment. Yet Davis cannot help but see human traits even in those animals he ends up hunting, and he repeatedly finds a human-like consciousness at work in the natural world, which we have irrevocably altered.

One of the welcome aspects of this new collection is Davis's insistence on highlighting those moments when humans tend to each other as well as to our environment. "By the Rivers of Babylon" finds a community looking after a boy in deep mourning:

The father of a boy my son plays basketball with

overdosed last week. Out of prison less than two days, he slid

the needle into that place where he wanted to feel something

like God and pushed the plunger of the syringe. The boy isn't any good

at sports, but when the coach subs him late in the game, score

already settled, we cheer wildly, as if he's performed a miracle . . .

"At the Raptor Rehabilitation Center"—a poem I would read solely on the basis of the title alone—shows us a dedicated attendant who goes above and beyond to take care of injured birds:

. . . The woman who feeds them,

who cares for their every need, wakes before the sun

and strokes the knife across a stone, hoping the chickens

she sacrifices will feel the mercy in a sharpened blade.

Even here, in this place of caring, a bit of "sweet brutality" must intercede: Something—in this case, the chickens—has to be sacrificed to ensure the raptors receive the sustenance they need to go on living and healing. Yet as the final lines attest, such killing is necessary, and the "simple offering" of it does not go unnoticed by the raptors (or the speaker of this poem, for that matter):

. . . Long before the school busses

arrive, or families in station wagons drive through the gate,

talons rip death's gift, and these birds sing riotous hymns

of praise for the sweet brutality in this woman's hands,

for the simple offering her loving kindness brings.

Davis might have ended this poem satisfyingly enough with the penultimate line ("of praise for the sweet brutality in this woman's hands"), but it is much more important for him to name these tender attentions, to call out the "loving kindness" she so clearly embodies.

In "Carnivore," Davis pays similar homage, in his dreams at least, telling us: "I slept, and in my sleeping / became the things I loved / and killed." What follows is a litany of the thinking, feeling animals he has hunted and consumed: "More than twenty / deer. Nearly fifty cows. Eighty-five hogs / and thirty-one lambs," and so on. Once again, Davis writes not from a place of guilt or shame, but out of a sense of duty and an ongoing need to honor these living things that gave their lives so that he might be fed:

Countless rabbits

longing to mate in their dens,

and ninety-three squirrels

searching the tree-tops

for leafy nests . . .

Gratitude and wonder radiate from each of Davis's poems, rendering them sacraments for readers lucky and openhearted enough to receive them. Surely Winterkill will solidify Davis's reputation as one of our most fearless, attentive chroniclers of the natural world, which he shows, over and over, must also include humans. Whether describing "the bones of animals" or capturing the way the last light of day brightens an apple, Davis reminds us that "We will all be ghosts to someone," and it is up to us whether or not we let our souls speak for us in the meantime.